When Prince Siddhartha was born, a prophecy foretold that he would renounce his inheritance and become a great teacher. Terrified of the prophecy coming to pass, his father the king surrounded him with comfort. He arranged for the streets to be filled with healthy people, so that the prince would not be troubled by any unpleasantness.

But Prince Siddhartha was troubled, nonetheless. When he was a young man, he made a trip outside the palace in his chariot, where he encountered an old man, a sick man, and a corpse. The experience changed his life. He reflected upon it, and realised that no matter how fortunate, secure or sheltered our lives are, there is no way of escaping old age, sickness or death.

He left the palace and became a homeless mendicant, eventually achieving enlightenment and becoming the great teacher that was prophesied. He became known as the Buddha. At the heart of his teaching was the concept of impermanence, that we should live our lives as fruitfully as possible for the short time we are here, and not fear death.

Buddhists generally have a mature attitude towards death. Many of them also have a mature attitude towards dead bodies, seeing them for what they are. They make a distinction between the body itself, which once provided temporary accommodation for a life, and the life itself.

Perhaps because we lead more sheltered lives, in the West we seem less comfortable with dead bodies. We tend to be either squeamish or ghoulish about them, unable to make the distinction between the body and the life, or unable to make the connection. Many of us are afraid or offended by dead bodies, but this horror fades as the corpse becomes harder to identify. We might be shocked to learn what a pathologist does when carrying out an autopsy, but have no problem with an archaeologist analysing a skeleton from the long-distant past.

One of the things that shocks and surprises people the most when I tell them about my Everest climb is that I had to walk past dead bodies on my summit day. Why have they not been removed and sent home for burial, people ask?

But before I answer this question, I’m going to debunk a popular media myth: the one that says that Everest is piled high with dead bodies. It’s an important myth to debunk, because it is used to provide evidence that climbing Everest has become inherently unethical. People with a grudge against those of us who have climbed Everest believe it proves that modern-day Everest climbers are bereft of conscience, stopping at nothing to reach the summit and “conquer” the mountain. People use the word hubris in reference to Everest climbers, believing the bad luck or poor judgement that resulted in tragedy must be a result of arrogance.

Leaving aside the non sequiturs, the premise itself is false. Everest is not piled high with corpses, any more than the surface of Antarctica is paved with the corpses of explorers from the Shackleton era.

It’s true that over 200 people have died on Everest, and the bodies of the majority are still on the mountain. But Everest covers a vast area. The majority of the bodies are hidden from view on the North Face and Kangshung Face, or deep in crevasses on the Khumbu Icefall, places so inaccessible that they might just as well be buried hundreds of metres underground, for all the likelihood of anyone ever stumbling across them.

The best example of this is Sandy Irvine, who died with George Mallory on the North-East Ridge in 1924. Some people believe that if they find his body they can retrieve a camera that will prove once and for all whether the pair made the first ascent of Everest. For nearly 100 years they have sent search parties to scour the North Face, studied it with telescopes, aerial photographs and satellite imagery in the hope of finding Irvine’s body. All of these searches have proved fruitless, and in all likelihood the body will never be found.

There are far more corpses, and in much greater density, in my local cemetery. Sure, they are hidden from view, but they are all very evident from the hundreds of headstones that mark where they are buried, and my feet pound not two or three metres from them every time I walk through it. And in any case, that’s not really the point. They’re still dead people like you and I, who once had hopes and dreams.

So let’s start by disregarding the tabloid headlines. Everest is not piled high with corpses. Less than 300 people have died there in 100 years. There are hundreds of places in the world that have borne witness to many more casualties than this. What shocks people about Everest is that the bodies have not been removed and taken to a place considered more suitable. So why is this?

Upsetting as it may be, the simple fact is that in most cases it is logistically impractical to move them. Helicopters cannot operate in the thin air of Everest’s North-East and South-East Ridges, and in the case of the Tibet side they are banned by the Chinese government.

It takes several strong climbers to carry a corpse back to base camp, or to a place where they can be given an adequate burial. Most climbers on the higher slopes of Everest are treading a fine line between life and death. Their first priority is to get themselves down safely. If they are confident enough of that, then their next is to help the living. A dedicated expedition to climb the mountain and bring down a corpse would cost a family tens of thousands of dollars, putting other lives at risk in the process. Insurance policies will generally cover search and rescue for the living, but they stop short of evacuating the dead from inaccessible locations.

The bodies of climbers who died in falls may be unreachable, and those who have been there a long time may be frozen in place. When a research team found George Mallory’s body below the North-East Ridge in 1999 it took five strong climbers over an hour on dangerously steep terrain to chip away the frozen gravel and rock that encased it, and another 45 minutes to gather enough rocks to give him a decent burial.

In many cases families and friends are coming around to the feeling that it’s better to leave bodies where they lie, high above the clouds. There is a story about climbers who recovered the body of Art Gilkey from a glacier in Pakistan in 1993 and took it home to the United States for burial. Gilkey died in a fall on K2 in 1953. When his expedition leader Charles Houston heard about the discovery during a lecture at the Banff Mountain Film Festival, instead of showing gratitude he said without emotion that he wished they had left him there.

The bodies of those who died of exhaustion beside the trail are often moved out of view. This usually means pushing them down the North or South-West Faces, or over the Kangshung Face into Tibet. This happened with David Sharp, the British climber who died on the North-East Ridge in 2006, whose body was removed the following year at the request of his family. It should have happened with an Indian climber called Tsewang Paljor, who died in 1996. His body remained in an alcove on the North-East Ridge for nearly 20 years, though I understand it has now finally been removed.

Nevertheless, people die on Everest every year, and in many cases their bodies still remain the following season. If you get as far as summit day on Everest, you will find yourself in one of those rare environments where you are almost certain to see corpses.

If you have read my book Seven Steps from Snowdon to Everest, you will know that I had to pass several on my Everest summit day, but I did not get fixated on them. Walking past corpses formed only a tiny part of a ten-year adventure.

I saw the bodies for what they were. Most that were on the trail looked like they had died from exhaustion, and I could understand only too well how they came to that end. I felt deeply for them; I understood how they had suffered. If anything they focused my mind and ensured I returned safely, so that my friends and family would not have to bear the loss theirs had.

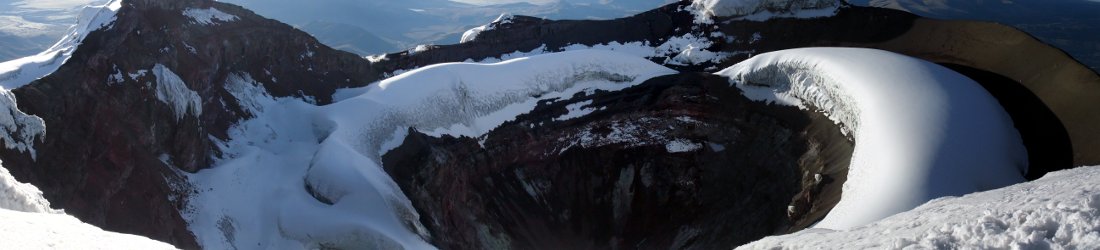

I ask that you view the photograph below in this context.

Some people who hear about the bodies lying on Everest say that the mountain should be closed to climbing, and left as a memorial to those who died. I don’t fully understand this attitude, but I believe it arises from a lack of empathy with those who climb. People who climb Everest are aware of the risks they are taking. They choose to accept the risk because the activity and the achievement enriches their lives. Not everybody believes the risk is worth the reward, but that’s their choice too. It’s not their place to interfere with the choices of others. I don’t know a single climber who would want to see a mountain closed to others and left as a memorial to their memory, simply because they took the risk and their number came up.

Perhaps it would help if people saw climbing Everest as a metaphor for life. If you want to experience it, you have to accept that you are going to see dead bodies sometime during your life, because death is a part of life’s fabric. It helps to have a more mature attitude, and see the bodies for what they are. Every death is a tragedy for someone, but death is also a part of our existence. It touches us all throughout our lives, and each time it does we can learn to be more compassionate and become a better person.

There are no jokes in this week’s blog post. I am sorry about that, but I hope you understand.

Would you take the same view if the ascent of Ben Nevis, or Scawfell or The Wrekin involved passing several dead bodies along the way? Would you not be worried if on your walk through that cemetery you encountered unburied bodies lying on the gravestones?

It is easy to reach the conclusion that Everest climbers quickly come to think that the fact that it has cost a lot of money to get onto the mountain and that they may get another chance justifies the suppression of the normal decencies regarding dead and dying people.

Charlie Houston might regret the recovery of Art Gilkeys body in 1993 but 40 years earlier he and his companion were happy to put their own lives on the line – a very fine line – to get their dying companion down the mountain. I

I don’t think you read the second half of this post, Mr Brown. Either that or you chose to ignore it. The post answers your point in some detail.

If you are familiar with Art Gilkey’s story you will know that his teammates made no attempt to find or recover his body. Once they knew he was gone, their first and only consideration was to get themselves off the mountain safely.

As to helping the living (which is not the subject of this post) people help each other out on Everest all the time. In that extreme environment teamwork is very important. This is just as true of modern expeditions. Heroic rescues happen frequently, with commercial teams working together to bring people down safely. These incidents go largely unreported because they are not considered newsworthy. In your haste to judge you appear to have overlooked this, or perhaps you are unaware.

Good post Mark as always-a thoughtful examination of one of the controversies around summiting Everest. I admit I find the idea of those bodies lying out in the open a bit creepy but get that they can’t be easily bought down. To me they seem testament to man’s folly as I can’t imagine wanting to die climbing a mountain but I respect that for some it’s clearly a big ambition.

Mallory (his body) was found, was he/it not?!

Check that, I re-read the article 😛

You make some reasonable points Mark about the variables that surround dead bodies in terms of human burial and nature’s own burial such as those by the 3rd step.

It would be similar to a person who died (hypothetically) on the moon in the past.

Would it really be worthwhile to send a fresh space flight to retrieve the dead if they were stranded on the moon?.

Everest is similar.

I note your comments about the search for Irvine and I agree with the subtext of your assessment; where even if he were to be found, after 92 years, the prospect for the camera film viability is very low.

Your photography again does make the mountain more accessable to the outsider viewer.

Thank you.

Mr Horrell

I have read all of your article several times and i don’t find an answer to the question I asked in my first paragraph. And I don’t lack empathy with climbers. In my youth I did a lot of climbing, albeit only in Europe. I was a member of a Mountain Rescue Team for thirty years and have carried off enough dead bodies not to be squeamish about them.

I appreciate that it is often, as in the case of Art Gilkey, not possible to evacuate or even search for a missing climber. But your contention that stepping over dead bodies in the self gratifying pursuit of a summit makes one a better and more compassionate person is hardly convincing.

Your first paragraph is crass and not relevant. It shows a lack of understanding of conditions high on Everest, despite the care I have taken to explain them in the post. The Wrekin, a wooded knoll rising gently above Telford?

You have a twisted mind, and you clearly enjoy twisting the words of others to fuel your hate. I feel sorry for you.

Who talks about “stepping over dead bodies”? You do. I said I walked past them. I mentioned moving them discretely off the trail. Stepping over them? That’s tabloid talk.

As for the line you dreamed up about stepping over dead bodies making you a more compassionate person? You need help, Dave. My words are wasted on you. Go and troll somebody else’s website.

Other haters, please read the commenting guidelines before posting:

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/guidelines/

Pingback:Zehn populäre Everest-Irrtümer - Expeditionen - Abenteuer Sport - DW.COM

Great article. It certainly will help me answer questions that I struggle to answer.

Thank you for the article .Although I myself

Would not have it on my wish list to climb Everest I can at least understand why someone might have the desire too.

Reading the article.from a person who has experienced Everest seems to bring a better understand then those who have written articles from a second or third hand account of the experience

Simone

Many people with lots of money,seem to refuse to accept their lack of ability and unfavorable conditions and get others killed too, is it really mature-to “adjust death” to make room to EXPECT-to summit because money was paid?,or to claim its all personal responsibility and competence ,and endanger porters who carry your laptops generator,gin and tonic for the summit,and set lines all the way and guide your unfit feet over each crevasse?

This entire controversy might be an outgrowth of wealth and greed predictably bringing the worst and lowest ethical standards- by treating these places as a -me- achievement shop in the exclusive mall. It doesnt seem to be present so much where the only way to get there is to carry everything yourself and be genuinely self reliant. Many people now clearly,undeniably,have a history of not- helping the living-when they could,and claim to be self reliant and responsible in imitation of historical figures,but were none of these things. If we research climbing aconcagua,you must pass a doctors medical at the start of the climb,and you can forget about porters and servants,there are only guides who can- effectively decide- its “no go”. Somehow,these communities still benefit from mountaineering and tourism without these things. A better form of natural selection is to ban anyone who cannot physiologically survive long enough to have options in the death zone and to eliminate large numbers of -not serious enough to transport by their own hand-adventurers.

when we use or quote from Bhuddist,Tibetan,and Nepalese,or even Hunza culture to justify things,lets finally be honest enough to admit they traditionally see mountaineering-climbing mountains as a sacriledge,that trespasses upon and provokes mountain dieties, and should seldom be undertaken.

Mark, thanks for a thoughtful and sensitive piece.

On a happier note; do you think that Mallory and Irvine made it before they died?

I can see the immature attitudes towards death in these few short replies, no wonder you took down the HR image of the summit. The corpses are merely shells of what once held a life full of hopes , dreams and strong opinions like the commentators here. There is nothing offensive about looking at one. While incredibly sobering to view, suggesting that you should eschew the mountain and turn back in horror is akin to someone saying “Oh my, I simply cannot drive on roads anymore, it’s disrespectful because hundreds of people die every year on this asphalt and the vehicle I am sitting in has become a deathtrap for many before me”.

If someone wants to do something, then erecting bans through barriers won’t stop them from doing said thing. Every second year someone hops into a boiling mud lake despite the signs or runs onto glacier. With all that training time the climbers for Everest surely gave a lot more forethought to the risk they were taking.

@Dave Brown,

The tallest of those topographical features you mentioned, Ben Nevis, and Everest is nearly 7 times as high.

At that height there is only a third of the Oxygen in the air available, and supplemental oxygen maybe gives the effect of reducing the effects of lack of oxygen by around 300/350 metres; note, people are NOT breathing solely oxygen but supplemental oxygen, they are still breathing reduced amounts of oxygen as compared to sea level, I doubt event he world’s most efficient marathon runner would be able to run a good time at the kind of altitudes I am talking of.

They are also encumbered by the other physiological effects of altitude, the 1924 expedition where Mallory and Irvine failed to return had one expedition member nearly choke on what was found to be frostbitten lump at the back of his throat. Then there is the clothing and not to mention that the path they walk is restrictive in that at points a foot wrong could be injury and possibly death, which can add to the psychology of failure.

Now, next time you go to the Ben, try and replicate the effort of Everest by carrying a backpack of around 3.5 to 7 stone (a poor approximation of the effort on Everest, but a start), depending on your size, plus all the clothing, equipment and oxygen kit, stay on a fixed route, knowing that a wind gust or wrong move at points will make you a statistic, with the added restriction of protection from snow blindness.

As you walk closer to the top of the Ben your heart is bursting, every step takes iron-willed determination, you are wondering if you can make it, but can’t think that far ahead, your only thought is the next step, probably the agony of the next step, so tired you can’t make that decision to go back, your focus is only the next step, then just short of the summit, in near exhaustion just off to the side you see someone, you can’t shout, you are too tired, if you stop your momentum is gone, but for a second you think ‘Are they OK?”…then it hits you, to reach them you have to go down off your path, more effort, then if they are still alive, and IF you reach them alive, how can you get them back to the path? You already know every step up was agony on the path, it will be worse off path on the steeper slopes back to the path. If your brain is still working properly you know that it is probably impossible for you to get back up to the path if you go down, and that is IF that person is alive and able to assist themselves back up to the path, if not, you risk death trying to bring them up.

At those altitudes for most people every step is survival, there are many accounts of people who stopped ‘to rest’ who died, to stop on Everest is death…unlike on the Ben, local volunteers are not available to get you off of the mountain, like that silly girl in her shorts taking a selfie a year or so back on the Ben.

On Everest you are alone, the only person who can help you out is yourself.

Think about it, a helicopter can’t operate up there the air is so thin, if you were in an aircraft at that height you’d black out in minutes if the cabin leaked (OK, so you are not acclimatised, but even acclimatisation only helps so much), and you think someone can just pick up a body in some kind of fireman’s lift and come down safely?

Everyone that goes on Everest knows it can be a one-way journey, it is drummed into them, you have to be in the peak fitness of your life, I have seen many unfit people walk up the Ben…it’ll never happen on Everest.

You speak of Ben as if he were a good friend. Ben Macdui, Ben Lawers, Ben Lomond?

My reaction to photos of dead climbers and poor George Mallory, with his clothes eroded away, head buried in rocks, is profound sadness, after the first twinge of horror. I understand that there are people who have a strong need to challenge themselves, even at risk of death, like anyone who climbs this frozen mountain, or parachutes from a plane, or walks a high wire without a net.

This is something that gives them what their spirit needs. They are brave beyond words.

Still, the dead bodies on the mountain are sad and pathetic; they lack dignity; they look like so much trash that was thrown away.

Of course it would be foolhardy to risk people’s lives to recover them, but is it possible to just cover them or pile rocks on them so they are honored and remembered in some way, without endangering another person? I think that the human body deserves respect, because it once housed a human soul, and these poor souls’ bodies have none.

Another question which puzzles me – How can these climbers be “unknown”? Is it possible that fellow climbers did not know when a member of their group didn’t come back? How is it possible that some of these people are unidentified? Do people climb up alone?

> is it possible to just cover them or pile rocks on them so they are honored and remembered in some way, without endangering another person?

Yes, and if they are are accessible they usually are. This may take some time though, as most climbers who pass by don’t have the energy to carry out hard physical labour at that altitude. The climber known as Green Boots is an extreme example. I don’t understand how he was left there for so long, though I would not have been able to move him when I passed.

> How can these climbers be “unknown”? Is it possible that fellow climbers did not know when a member of their group didn’t come back? How is it possible that some of these people are unidentified? Do people climb up alone?

As far as I am aware, all fatalities on Everest have been reported. Most climbers are identified. Those who aren’t are those who were climbing alone.

In all my reading on Everest I wonder how George Mallory’s wasn’t stumbled upon before?

Was he just way off the usual routes people take?

Surely in all the 100s of people and 70 odd years someone down the line would have seen him?

Yes, that’s correct. He was way off the normal route on steep, technical ground on the North Face. There is no way anyone would stumble that way unless they were looking for him. It’s a huge area, and in the big scheme of things, only a relatively small number of people have passed up the North-East Ridge a few hundred metres above where he lay.

I find it very difficult to have sympathy for people that die on Everest. To me, it seems rather selfish to put yourself at such great risk knowing there are people that you love who will be devastated by your death.