The most talked about subject in Britain at the moment isn’t the upcoming London Olympics, but the crap weather we’ve been having. First it was the wettest April on record, then it was the wettest May on record. I happened to be out of the country for the whole of April and May so I missed all the fun, but no matter. It was the wettest June on record too, and July’s also doing a good job of keeping the ducks happy.

I decided to head to Scotland, a place that’s renowned throughout the world for its bad weather. When it rains pretty much every day in London you might as well. At least the scenery’s better, as long as you can see it.

As a token gesture I’d been keeping my eye on the weather forecast on the off chance things improved briefly, and I was rewarded with a possible window of opportunity when things might be clear on the summits. The Met Office website has recently had a revamp for the better, and now allows you to see what the weather’s going to be like not only in selected areas of the country, but also at specific weather stations dotted around the hills. I’d been following the forecast for a peak called Ben Dorain, across the valley from the Black Mount area I’d earmarked for my walk, and was therefore receiving reports of the likely weather not at sea level, but at 1074m on top of a Munro. A three day window during which the summits of the peaks were all predicted to be out of cloud was enough to get me packing my rucksack and heading north.

It took most of Wednesday to drive up from London, so I stayed the night at the campsite in Tyndrum, a tiny village of B&Bs, campsites, a petrol station and a pub on the main road north. I had a welcome burger and chips in Paddy’s Bar and Grill that evening, washed down with a couple of pints of McEwan’s 80 Shilling ale. Less happily some wag decided to put a non-stop diet of old Proclaimers songs on the juke box, so I had I’m gonna be the man who’s havering next to you ringing round and round in my head in a comedy Scots accent for the next three days. This was only marginally less annoying than the midges, of which more later.

The following day I drove the ten miles or so up the road to the Victoria Bridge car park beyond Bridge of Orchy, close to the shores of Loch Tulla. The West Highland Way passes through here, and many people were camping wild in the flat grasslands on the western end of the loch, but although it was 8 o’clock I was surprised to see nearly all of them were still sleeping. I was pleased not to be heading north with the crowd, however. One of the attractions of wilderness backpacking is the peace and solitude, and the route I’d chosen was much quieter. In fact, it was to be many hours before I saw another person.

I headed west on a broad track in the wide flat valley of the Abhainn Shira before turning north up a side valley between my two first Munros, Stob Ghabhar and Stob a’Choire Odhair. I ascended gently through boggy grassland to begin with, but at the foot of Stob a’Choire Odhair, the path steepened up a ridge. I plodded very slowly with my backpack, and I kept looking back expecting to see other walkers catching me, but it soon became clear these hills are not so popular during the week. My only company for the next few hours were frogs (hundreds of them, all camouflaged, and quite suicidal, appearing suddenly as a flash of movement beneath my boots) and red deer (much more wary and hard to get within 50 metres of, probably because hundreds of them are culled every year during deer stalking season).

As I approached the summit of Stob a’Choire Odhair (Peak of the Dun-Coloured Corrie, 945m), the cloud which had been crowning the summits for the early part of the morning began to lift as the sun tried to burn its way through. I dropped 300m to a col at the tee of two perpendicular valleys. As I passed across the other side to a gentle buttress leading up to Stob Ghabhar’s summit ridge, the sun pierced the cloud and there was a ‘wow’ moment when I looked behind me and saw Rannoch Moor stretching beyond the far horizon. A featureless highland bog stretching for miles, Rannoch Moor has a fearsome reputation as a place to avoid when the clouds descend, where navigation becomes very difficult. The eastern end of the Black Mount hills rise directly above it and on a clear day like today give as good a view across it as you can get. From where I stood it had the appearance of a vast wetland habitat, flat and grassy, and strewn with many lakes. I was looking all the way across it to the hills of Ben Alder far beyond.

The sun remained as I climbed to the top of Stob Ghabhar, which I reached by means of a moderately rocky ridge which curved around to its summit. At 1090m Stob Ghabhar (Goat Peak) was to be the highest point on my walk, though only the 55th highest Munro in Scotland. It was very pleasant and sunny at this moment, and I could see all seven Munros I would be climbing right across to Ben Starav in the far west. To my north stretched the dramatic rocky hills of Glen Coe, and I could just make out Ben Nevis to the north, the only peak still in cloud. A broad rambling ridge nearly three miles in length stretched before me, sloping gradually downwards to the west.

It was now 1 o’clock and I needed a sandwich. As I chomped away I discovered how Goat Peak came by its name: goats have fleas and my lunch was teaching me something about midges. They’re hard to avoid in the lowlands of western Scotland throughout July and August, but you can usually escape them by climbing a hill. It’s not the altitude they object to, though, but the wind, as I was about to learn. Even a gentle breeze on a hillside is enough to send them away, but it was so calm today that as I ate my sandwich more than 3000 feet above sea level, I was turning into something of a tasty meal myself. I’ve never come across midges on the summits of mountains before, but the pesky little fellows weren’t going to restrict themselves to Goat Peak.

The ascent of Stob Ghabhar was the only real sun I got during this walk. As I traversed the ridge beyond, the clouds thickened overhead and everything became a bit dull. But happily the clouds were high and the summits remained clear: I was still able to see where I was going. It took me nearly two hours to walk to the end of the ridge, and it was very pleasant and easy walking for a time. Meall Odhar, the western limit of the ridge, was marked by a cairn. I stopped for a short rest here before embarking on some rough scrambling 250m down a wet grassy hillside to Lairig Dhochard, the col linking Meall Odhar and Meall nan Eun, my next Munro. It was very steep and I had to tread very gingerly with my pack on my back, prodding the ground in front of me with my trekking pole. A slip here would mean more than an uncomfortable slide on my backside. It was one of those slopes you look back at and wonder how you got down. You certainly wouldn’t be tempted to climb up it if you were coming the other way. I had been studying the slope up the other side on my way down. It looked similar, and there was a band of rocks across it that might prove to be a barrier, but when I got there it wasn’t as steep as it looked. It was very wet and boggy, and after eight hours of being entirely alone among the hills, I was amazed to see another person coming down it.

The rough ascent didn’t last long, and the summit of Meall nan Eun (Hill of the Birds, 928m, which I learned later is pronounced meal-nan-ain, rather than meal-nan-ooooon, as I’d been saying to myself in a stereotypical Proclaimers-like accent) turned out to be a wide plateau marked only by a single cairn at one edge. I had the rest of my lunch to finish here, and I ended up having to eat it standing up as I strode around the plateau trying to avoid the pesky midges. They really have no right to be up the summit of a Munro. Yes, I know, they’re an important part of the food chain; ducks eat them, we eat ducks and they eat us. In fact it’s not so much a food chain as a food noose. As I tried to eat my sandwich while they chased me round the summit, I couldn’t help but think their existence is pointless. I’m sure I could exist quite happily without them and feed my sandwich to the ducks instead.

I didn’t have far to walk that day after Meall nan Eun. I crossed the outlying peak of Meall Tarsuinn and dropped to a grassy col of stagnant ponds beneath Stob Coir an Albannaich, my next Munro, and decided to stop here to camp. Stob Coir an Albannaich (Peak of the Scotman’s Corrie, 1044m) looked rocky and forbidding as I approached, and again I looked for a way up it as I descended Meall Tarsuinn. It was clear this afternoon, but everything might be in cloud tomorrow morning, so it was worth looking for the path beyond before I turned in for the night. Three parallel ramps in the rock face appeared to offer possible routes of ascent, but when I reached the bottom I discovered they were quite broad gullies which were actually quite straightforward to ascend. The middle, most promising, one even had a semblance of a path up it.

Back on the col I listened for the sound of running water. Somewhere underneath the ground there must be many channels, and I looked for the places where they ran across the surface and formed narrow streams. After about ten minutes of looking around for likely sites to pitch my tent I found a flat area of dry, shorter grass within ten metres of a narrow channel which offered me fresh running water on tap. It was only around 5.30, and I pitched my tent and settled in for a comfortable evening brewing up copious quantities of tea, a Wayfarer meal of beef stew and dumplings, and a few chapters of my book, Penguins Stopped Play, about a village cricket team playing matches on every continent (including, as you will deduce from the title, Antarctica).

I was packed up and ready to leave at 7.30 on Friday morning. As I had feared, I was in cloud, but I set off up the gully which joined a gentler ridge after about 150 metres of ascent, and I was on the summit of Stob Coir an Albannaich little more than an hour after setting off. Here I found myself deep in cloud and I had to fish out my compass to point the way southwest down a wide gentle incline. After about ten minutes of descent the next peak, Glas Bheinn Mhor (Big Green Hill, 997m), started emerging from cloud and I could see the way forward. I put my compass away, and this was the only time during the walk my navigation was tested. The gentle slopes before me were teeming with red deer, but before I was anywhere near them they noticed me and started dashing down the hillside in herds. I felt like a Welshman in wellies crossing a sheep farm.

By the time I found myself above the narrow neck of a col attaching Stob Coire an Albannaich to Glas Bheinn Mhor I was all alone again. The descent to the col was short, and there was a clear path up the other side, ascending steeply and then more gently as it merged into Glas Bheinn Mhor’s summit ridge. I was on the summit of my next Munro by 10.30, and the weather was threatening to improve again, as it had the previous day. I could see another broad ridge somewhere below me that continued into a steep escarpment up to Ben Starav, the westernmost Munro of the Black Mount hills, via a smaller peak, Meall nan Tri Tighearnan (and if you know how to pronounce that, award yourself a venison steak). Ben Starav itself was in cloud, but above it there was blue sky. To the south, across the head of another valley, Glen Kinglass, was an outlying Munro, Beinn nan Aighenan, which I would be climbing at the end of the day.

The blue sky ended up being a tantalising glimpse. As I descended Glas Bheinn Mhor down to the ridge the sky became grey and gloomy, and remained so for the rest of the day. By the time I started climbing the escarpment Ben Starav was disappearing into cloud again. I plodded up slowly and reached Stob Coire Dheirg, the first of three individual peaks on Ben Starav’s summit ridge, at around midday. The first part of the ridge was something of a knife edge scramble which I wasn’t interested in doing with my heavy pack, so I found an easy trail a few metres below. I was deep in cloud now, and as I reached the second unnamed summit the heavens opened. I stopped to put on waterproof trousers, rucksack rain cover and Gore-Tex shell mitts over my gloves. Visibility was down to just a few metres and I knew I was back on the tourist route when figures began appearing out of the mist.

1078m Ben Starav rises above the picturesque Loch Etive, and probably would have had the best views of the walk, but by the time I reached the summit I could see pretty much bugger all. My summit photo could have been taken anywhere. I reached the top at 1 o’clock and turned around immediately to descend the way I had come. An hour later I had descended out of the cloud and was back at the foot of the escarpment eating a sandwich of ham, cheese and careless midges. As I crossed the head of Glen Kinglass to Beinn nan Aighenan the cloud lifted off Ben Starav again, it’s job done (of dumping its load onto the mountain for the precise period I was up there).

My aging knee gave me some jip as I climbed up Beinn nan Aighenan, and I was forced to ascend very slowly. It was 5 o’clock when I reached the top, and the sky was dark and gloomy. All the summits, from Ben Starav right across to Stob Ghabhar in the far distance to the north, were clear. The rest of the view was pretty amazing too, mainly to the west, where Loch Etive lingered as a white streak within a frame of dark hills far below. I could even see right across the Firth of Lorn to the Island of Mull on the far horizon. A dark summit rose up right in the middle of it, which I assumed must be Ben More, Scotland’s only island Munro outside of the Isle of Skye.

Glen Kinglass loops around Beinn nan Aighenan, surrounding it on three sides. I had intended to descend to the south and walk up it to its eastern flank before finding somewhere to camp, but it was now quite late in the afternoon and the darkening sky looked threatening. From previous experience I knew the guide book I used to plan the walk, the Central and Southern Scotland volume of Graham Uney’s excellent Backpackers’ Britain series, tended to err on the strenuous side of hardcore when estimating walk lengths, too tough for me in any case, and it may take many more hours to reach its suggested overnight spot. About 200m below the summit I spotted a broad corrie full of little lakes which had the look of a wild camper’s paradise. Without hesitation I descended into it and pitched my tent on a flat stretch beside the largest of the lakes. About half an hour later it started tanking down, and the rain pounded on my tent for the next two hours. By then I was a couple of chapters through my book and had several mugs of hot tea inside me. I had timed it perfectly and was pleased with my decision to stop early.

The next morning, Saturday, I had even more cause to be thankful. I left my lochan paradise a little before 8 o’clock and it took me two hours to descend into Glen Kinglass, on very steep slopes of tall grass disguising hidden hollows. I had to take great care not to twist an ankle or slip on my backside. The tall wet grass left my feet and legs sodden up to my knees, and there would have been nowhere to camp on the steep slopes. Had I continued past my campsite I would have been descending hazardous slopes throughout the rainstorm and reached the bottom dressed in a haddock’s bathing costume.

It was a straightforward walk through Glen Kinglass on a good track until I reached its eastern bend at its confluence with the Allt Coire Beithe. I passed a footbridge which wasn’t marked on the map about half a mile earlier, but my Ordnance Survey map showed another footbridge at the confluence, which I could clearly see across the boggy grasslands from some distance away. I was mildly perturbed when I started passing ‘Footbridge’ signs directing back to the one I’d passed half a mile back, but there was no way I was going to walk all the way back there. When I reached the marked footbridge I could see why the signs were there. It was rickety and derelict, half of its planks had fallen into the river, and there were no steps up to it and down the other side again. I had been duped. Why they hadn’t built a new bridge right next to this one heaven only knows. I’m sure I’m not the first person to be fooled in this way, and I can’t imagine any of us, having come this far, would see fit to make a one mile round trip to cross a five metre stream when there’s an alternative means of crossing, albeit a somewhat dodgy one, right in front of us. I put a foot on each wire suspension cable either side of the bridge and edged my way up. The boards that were remaining seemed safe and I walked along them until I was halfway across the bridge. The rest of its span I had to cross with a foot in each wire fence either side, and the hardest part was descending the steel suspension cables to ground level on the other side, as they were quite steep and slippery, but I made it bar a couple of minor grazes on each hand which I cleaned up with an antiseptic wipe after I landed. There’s a popular video that does the rounds on Facebook every now and again of Indonesian children crossing a collapsed suspension bridge across a swollen river to get to school. Compared to that my crossing was a relative breeze, though I would rather have done without it with my heavy pack.

I was into the western end of the wide valley where I started my walk two days ago. For the next three hours I walked to the south of the ridge of Black Mount hills I had spent almost the entire of those two days traversing, looking back up from the view I’d been looking down at for much of the walk. I felt like I was watching myself backwards in speeded-up motion. The highland route took two days; the lowland one just four hours. I reached the quiet black waters of Loch Dochard, where I rejoined the Abhainn Shira. Briefly the path nudged its way into a forestry plantation to provide some diversity to the scenery. A footbridge here had vanished completely, but the river was narrow enough for me to get across on stepping stones armed with my trekking pole to steady myself. I was back at Victoria Bridge shortly after 2 o’clock, and now I could see all the way down the line of Black Mount hills from my first Munro, Stob a’Choire Odhair, all the way to Ben nan Aighenan and Ben Starav at the far end. I’d only had one short rain burst to contend with on the summit of Ben Starav, and although the weather hadn’t been perfect – a touch dark and gloomy most of the time – in this British summer of record rain I had no compaints. The poor light meant that it wasn’t a great week for photography, but the main thing was the summits had remained clear and I was able to see where I was going, and in the Highlands of Scotland that means fabulous views. I boosted my Munro count to 81, which means I only have another 200 or so to go. It shouldn’t take me more than 20 years to accomplish this, give or take the odd decade.

I lost some weight too, mainly by being eaten. I learned that in this part of the world nowhere’s safe from midges.

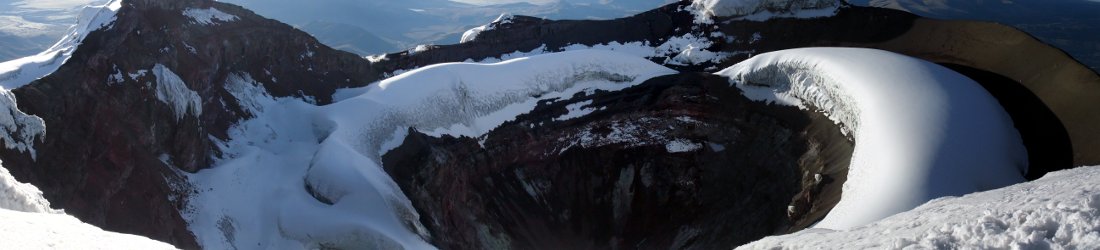

You can see the rest of my photos here, and here’s a little taster of the first part of my walk so that you don’t have to imagine it.

Excellent stuff Mark, I really enjoyed that. A detailed report with lots of good navigational information for help with planning future trips. I’m looking to do the Black Mount traverse, or a variation, at some point having really enjoyed the two Munros nearest to Victoria Bridge. Apart from the midgies and the odd patch of cloud that looked a good trip and the wild camp locations, particularly the second, sound good.

Great, glad you liked it, Nick. I really enjoyed the walk, and the views at each end were stunning, although I missed the one from Ben Starav. There are plenty of good places to camp and fill water bottles throughout the route aside from the two I ended up using.

Think you ve missed the point a bit! The best bit about this trail is all the people you meet along the way, it s very sociable. Go over Easter before the midges It s a sort of welcome to spring ritual loads of people walk it on a regular basis, and they re great company. And if you really want a bit of exercise you can follow the high level route

Missed the point? Do you think I go on these backpacking weekends in remote places to meet people? They have dating websites for that 😉