When I first read Jon Krakauer’s seminal disaster porn classic Into Thin Air 15 years ago it was a bit of an eye-opener. Back in those days I was a humble hill walker with only a passing interest in mountaineering and Krakauer’s autobiographical tale of a former alpinist who joins a commercial expedition to climb Everest on a reporting assignment and becomes caught up in the biggest disaster in Everest history struck a chord with me that sounded like a cat strangling itself in the strings of a violin.

Like many people who read the book soon after its publication I had always assumed Everest climbers were some of the most hardcore athletes on earth, and I had no idea relatively inexperienced people could pay to be guided up. I was incensed. I believed the world’s highest mountain should remain a pristine wilderness reserved for only the very best, and I had little sympathy for the presumptuous victims who pushed on to the summit long after they should have turned around, and lacked the resources or experience to get themselves down when they became caught up in a storm. I was staggered by the many examples of climbers ignoring their struggling team mates and saving themselves, and I shook my head at the catalogue of senseless blunders that heightened the tragedy.

Had anyone told me that a few years later I myself would be paying to join a commercial expedition to climb Everest in much the same way I would have phoned the emergency services and asked them to bring round a straitjacket. In the years that followed I read some of the alternative accounts of the 1996 Everest tragedy such as Anatoli Boukreev’s The Climb and Beck Weathers’ Left for Dead, and began to feel that Krakauer may have judged too harshly. I took up mountaineering myself, always with commercial expeditions, and I began to sympathise with the victims. I understood their motivations, and I learned that with enough experience amateurs could climb a mountain like Everest in relative safety. I became a fan of commercial mountaineering; it gave me many wonderful experiences that I wouldn’t otherwise have had, and I began to defend it staunchly against the attacks of alpinists and would-be alpinists [*] who held guided climbers in contempt. I started to feel that books like Into Thin Air encouraged the attacks by portraying commercial climbing in a negative light, and arming people who didn’t know any better with enough knowledge to make them feel entitled to criticise.

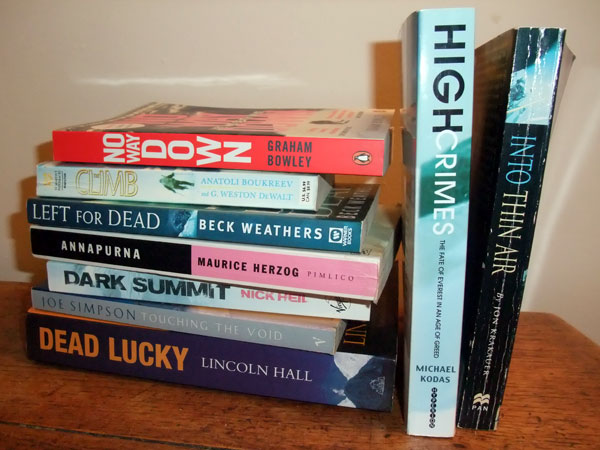

Since Into Thin Air came out in 1997 publishers have flocked to release books about mountaineering disasters. In a previous post I reported how a top 12 search for “Everest” on Amazon produced 7 disaster books, 6 of which were about the 1996 tragedy alone. Most of those accounts were by climbers who were on the mountain at the time but more recent disasters have produced books by journalists who had no interest at all in mountaineering until the tragedy happened. Nick Heil’s Dark Summit about the series of deaths on Everest in 2006, and Graham Bowley’s No Way Down, about the 2008 K2 disaster when 11 people died in a single day, are two such accounts. Both of these books are meticulously researched, extremely well-written, riveting reads that are actually quite fair and sympathetic to the characters involved, but every time I see a new book like this I can’t help wishing they had never been published.

Why? For me there are two reasons. Firstly because they tend to attract readers who are not familiar with mountaineering who don’t then go on to read other books on the subject which don’t involve disaster, people take their word as gospel. For example, the clients in Jon Krakauer’s Adventure Consultants team in Into Thin Air were from quite a narrow background. Most were wealthy professionals such as lawyers or doctors in their 50s, who had taken up guided climbing later in life, and were treated like children by their expedition leader. They moved very slowly on summit day and probably weren’t in good enough physical shape to climb a mountain as challenging as Everest. They have since become the stereotypical guided Everest climber, and while many do fit this profile, the vast majority do not. A typical Everest climber could be between 25 and 65. Most do not command lawyers’ or doctors’ salaries and will likely have spent years saving up or raising money in sponsorship to fund their climb. Some are true mountaineers, who have no need to be guided and are perfectly capable of making their own decisions, but have signed up for a commercial expedition to simplify the logistics and share costs (these days many people turn up on Everest having climbed multiple 8000m peaks). A great many are fitness fanatics, who may not have a whole lot of experience at high altitude but if they acclimatise successfully will end up moving quickly on summit day.

On another level many readers assume the events described are accurate, but this simply isn’t possible. No Way Down reads like a novel. Incidents on the mountain are described from the point of view of the climber involved, including thought processes which can only be conjecture. These are interspersed with descriptions of their life back home, in a less than satisfactory attempt to gain an insight into their reasons for climbing K2. There’s nowhere quite like an expedition peak for rumour and misinformation. Climbers bump into other climbers at base camp or on the mountain, and swap titbits they have learned second hand. Conversations are overheard on radios and misinterpreted. While a journalist will try to cut through this and figure out the most likely story, the combination of rumour, exhaustion and altitude sickness means high altitude mountaineers don’t make very reliable witnesses. Krakauer provided a chilling example of this himself when he believed he had witnessed a guide walk into camp safely only to learn months later that he had mistaken the person involved, and the guide had most likely died long before reaching camp. I can vouch for this faulty recall myself. I usually type up my diaries months after returning from an expedition, and frequently I find what I have written immediately after the event differs significantly from how I remembered it.

But the main reason I don’t like disaster porn is its capacity to incite hate. Death is an emotive subject, and when death is perceived to be preventable it provokes people to anger. In the final chapter of Into Thin Air, Krakauer quotes some of the angry letters Outside magazine received after publishing an article of his about the tragedy. Here’s one example:

“I agree with Mr Krakauer when he said ‘My actions – or failure to act – played a direct role in the death of Andy Harris.’ I also agree with him when he says, ‘[He was] a mere 350 yards [away], lying in a tent, doing absolutely nothing …’ I don’t know how he can live with himself.”

Ignorance and self-righteousness are an unpleasant combination. It’s unreasonable to pass judgement when you’re not able to put yourself in somebody else’s shoes, and the trouble with high altitude mountaineering is that it’s so far removed from normal everyday life that for most people putting themselves in the shoes of a mountaineer in a life or death situation is a near impossible task. Anyone who’s sat exhausted in a hurricane on a giant plateau in a near total whiteout may have some understanding of why Jon Krakauer was unable to move 350 yards to rescue a dying man. They will understand that those 350 yards might just as well have been 350 miles. But the writer of that letter clearly didn’t, yet he felt entitled to cast his opinion. In his introduction to Lincoln Hall’s Dead Lucky, another book about the disastrous 2006 Everest season, Lachlan Murdoch (who ironically is the son of one of the world’s great promoters of media-fuelled hate) recognises this when he says “no book or essay or lecture can expose an answer to something that cannot be taught or learned. It must be felt.” Lincoln Hall’s story of sudden near-total collapse and miraculous recovery after a night in the open at 8500m on the Northeast Ridge is hard to comprehend even for people who have been there.

When I returned from Everest myself two years ago I was stunned by the negative reaction in the UK media to the numerous deaths on the mountain that year. I posted a response to them, but my clumsy attempt to explain why climbers might be left to die on Everest’s summit ridge provoked a great deal of anger and hatred. Thankfully several readers helped me out, but I eventually had to close the comments.

Recently I stumbled across an article in the excellent To Hatch a Crow blog reacting to a BBC documentary about the 2008 K2 disaster. The article lambasted commercial expeditions as “commercial razzmatazz” designed for “well heeled clients … festooned with advertising logos” to ascend a “staircase of ropes” and “tick off one of the items on their bucket list”. It was a grotesquely twisted version of the modest stereotype of the commercial client first introduced in Into Thin Air. It’s a description that bears little resemblance to the great many very experienced climbers I have met on commercial expeditions, most of whom are not sponsored, have worked and saved for years for the chance to attempt a challenging peak, and have many honest reasons for being where they are. And this article was posted on a blog for people who know a thing or two about mountaineering. (To read about real people and provide some very welcome support for this blog, you could read my own account of climbing Everest as part of a commercial expedition, The Chomolungma Diaries.)

I recently re-read Into Thin Air, and I was surprised by how much my opinion of it had been coloured over time. In fact Krakauer was surprisingly non-judgemental. Unusually for an alpinist he sympathised with the commercial clients he found himself climbing with, and as far as pointing the finger of blame goes, he was wracked by the guilt of a survivor and as critical of his own actions as those of anyone else. The book has universal appeal precisely because he assumes the reader has no prior knowledge of mountaineering. The first half of the book doesn’t even cover the tragedy at all, and includes historical context as well as descriptions of the landscape and expedition life. The denouement is as powerful a piece of writing as you will find anywhere, and the raw emotion of a man caught helplessly in an unfolding tragedy oozes through every paragraph. It is probably the best-selling book about mountaineering ever written, and deservedly so.

So perhaps I’m being disrespectful by calling it disaster porn, but I make no apologies. I’m not referring to the quality of writing. There are many highly regarded works of literature that slip in a spot of titillation among the fine writing (I even studied D.H. Lawrence as an A Level English literature student). I don’t mind reading the odd bit of disaster porn myself (though just to be clear: I keep the book firmly in my right hand). There’s plenty of it out there, and sometimes it’s hard to avoid. Disaster porn doesn’t necessarily have to involve complete disaster either; near disaster will do. Two other classics of the genre are Joe Simpson’s Touching the Void, about a man who crawls for three days down a glacier with a broken leg after falling into a crevasse and being left for dead, and Maurice Herzog’s Annapurna, where the main protagonists escape with their lives if not their digits.

These are great books, but they are also porn because of the motivations of a subset of readers who get their kicks from reading about death and playing the blame game. These books and readers crowd out the many great books that celebrate mountains and mountaineering in a positive way. Too much porn is unhealthy and a distraction from the more fulfilling things in life.

So if you see a copy of Graham Ratcliffe’s A Day To Die For on your bedside table (which some people felt was one more 1996 Everest disaster book than we really needed), then maybe it’s time to bring your relationship to a swift conclusion and head out to the mountains for some peace and solitude.

And if you don’t agree with me then you must be a wanker.

[*] The term “alpinist” is loosely defined but is generally understood to mean mountaineers who climb unguided, and in a style that favours pioneering ascents, new routes and a lightweight approach. If you were being unkind you could say it’s a term that can be used to distinguish proper climbers from riffraff like me.

[UPDATE, JANUARY 2016: For a very different sort of mountaineering book, you may be interested in Seven Steps from Snowdon to Everest, my first full-length book, about my ten-year journey from hill walker to Everest climber.]

Nice article as usual Mark. With respect to Into Thin Air, I share your final conclusion. I also re-read it recently and came away with the conclusion that Krakauer was overall “fair and balanced”. Yeah a bit of hyperbole here and there to keep it entertaining but certainly not a dry documentary.

It also bothers me that some recent books by climbers, oversell their “personal disaster” and undersell that it was their mistake or fully credit/acknowledge others for saving their life. This may be the case with some historical books, but I have no way of knowing, obviously.

As the saying goes in journalism, “if it bleeds, it leads” Sadly this is what it takes to get the public’s short attention span. The best headline for Everest would be “Stripper pays Sherpa $1M to keep her from Dying on Everest” 🙂

I have to say that whilst I am somewhat fascinated with what I term as ‘mountain-death-porn’ it’s been reading books such as The Climb, Into Thin Air, No Way Down which has led to me learning a lot more about mountains, climbing and some of those involved – I’m currently reading Buried in the Sky about the 2008 K2 Sherpas and am learning a lot about this incredible group of people, Annapurna by Herzog, and Killing Dragons, about the conquest of the Alps.

I hope I’m not alone in finding that the disaster-porn you get in mountaineering non-fiction is a gateway into a whole lot of other fascinating books. I’ll keep reading the disaster-porn but I like to think that my armchair-climber understanding of events is shaped by reading other books like Annapurna, Touching the Void etc. I hope others graduate from the straightforward accounts of disasters and find the wealth of other fantastic work that’s out there.

Thanks, Jo, hear hear, that’s kind of how I did it as well. Killing Dragons – now there’s an interesting mix of disaster, history and humour. They don’t write many books like that.

I like the headline, Alan. You forgot to mention the world’s highest garbage dump, but what the heck, I’ll read it anyway. Now where’s the link? 😉

Nice topic Mr Mark.Horrell.I personally feel that the charm of climbing Mt Everest in the 21st century has been diminished as its conducted akin to a “PACKAGED TOURIST TOUR”. Main qualifications are a good bank balance and a reasonable amount of physical fitness with the courage of a adrenalin junkie.I myself as a ex-Marine engineer have seen enough of sea-adventure having survived cyclones and also sailing on “Coffin Ships(Badly maintained)”.After voluntary pre-mature retirement from the Merchant Navy i now travel on my own enjoying “Solo Backpacker Travel” as akin to the high seas i find it challenging.I will be visiting Bhutan, Darjeeling and Gangtok in a few days, a solo journey and have read your blog on Bhutan.At age 54 will be trekking to Taktsang Monastry a location which you consider one of the best in mountain treks.

Interesting train of thought, Mark. What makes Krakauer’s work so timeless is the first hand account that is lacking in the “scrubbed” third person narratives. (our local school system has incorporated “Into Thin Air” into their high school curriculum) Although the thoroughly researched books have good journalistic sourcing, it removes the emotion of day to day expedition life that makes, for instance, a Horrell read attractive and relatable.

Ha, thanks John, appreciate the compliment, but my adventures aren’t anywhere near as exciting as yours. 🙂

You’ve reminded me about Joe Simpson’s Twitter exchanges with students when Touching the Void was incorporated into the school curriculum here in the UK. It turns out not all teenagers enjoy disaster porn:

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/may/24/mountaineer-joe-simpson-twitter-row

if people want to climb mountains and kill themselves in the process that is their business. I do feel for the people who risk their lives saving these knuckleheads. this sport serves no real purpose other than endangering the participant and innocent people. that is why they have laws against knuckleheads climbing skyscrapers. what they should do is go up in a helicopter and swat them off, and then say anyone else, whose next. that would end the stupid behavior

Please can you read the commenting guidelines before posting again: https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/guidelines/

I just found your blog today after getting interested in mountaineering for the first time from reading some pre-2015 articles about it last winter, and re-interested by the upcoming movie. I agree with your assessment of Into Thin Air – Krakauer really is the most compelling storyteller I’ve read so far. The end of this post made me laugh, because I just bought several Kindle books on the subject of 1996, thinking it would be worthwhile to read some other perspectives as the media gets into it again… and the one I’m about to start is Graham Ratcliffe’s.

Graham Ratcliffe’s book is fine and certainly no worse than any of the other accounts of the 1996 Everest tragedy. I singled it out because it appeared years later, long after we thought the last word had been said. It’s actually slightly different from the other accounts, and is as much about the author’s personal crusade to uncover a certain piece of information (that the storm was predicted and the teams affected by it had access to accurate weather forecasts) than it is about the tragedy itself.

As it happened I should not have singled this book out. Since I wrote this post another 1996 survivor, Lou Kasischke, has published his own account, and then of course we have a Holllywood blockbuster movie released this week. I’m sure there will be plenty more produced to satisfy the public’s insatiable appetite for the 1996 Everest tragedy.

If disaster porn is your thing I should point out there have been other mountaineering disasters. I can recommend Robert Craig’s book Storm and Sorrow in the High Pamirs, about the 1974 Peak Lenin tragedy:

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2015/sunshine-and-optimism-in-the-high-pamirs-my-attempt-on-peak-lenin/

Hello Mark,

I recently came across your blog and have purchased a couple of your diaries. Very nice stuff to read.

For a different take on this genre of writing I would suggest “Deep Survival” by Laurence Gonzales. It does not cover just the disaster parts. It also explores the forces at play and the limitations we face as humans which lead to disasters. I found those discussions more fascinating than the disaster porn parts (although those portions were interesting as well).

Richard

If humanity goes out of the window above 8,000 metres, then humans should not go there …..

So it looks like you’ve missed the point of the article, which was to say that you should not judge mountaineers and mountaineering on the basis of what you read in disaster porn books.

There are many examples of heroism at high altitude, which don’t get written about as often as they should. Here’s one I blogged about recently to provide a more balanced perspective:

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2016/a-long-overdue-heroic-story-of-rescue-high-on-everest/