Britain’s greatest living mountaineer is currently touring the country presenting a series of lectures about his life, and I was lucky enough to see one of them last Friday at G Live in Guildford. An important World Cup qualifier was taking place that evening between England and Montenegro, but if Chris Bonington’s life were a football match it would be a 22 goal thriller which ended 11 goals all and went into extra time. It wasn’t difficult decide which of the two events I was going to go and see.

But how on earth was a 79 year old man who has been climbing for over 60 years, completed many first ascents in the Alps and further afield, and led some of Britain’s most iconic expeditions to the Himalayas going to compress his life into a 90 minute slideshow presentation?

The answer was a hair-raising, breathtaking, guffaw-inducing, roller-coaster journey around the world’s great mountain ranges, involving a star-studded cast of some of the most colourful characters in British climbing over the last 50 years. I don’t know how I’m going to fit it into a 3000 word blog post, either, but I’m going to try.

Like many British climbers, Sir Chris’s involvement in mountaineering began on Snowdon at the age of 16, when he and his schoolmate Anton hitch-hiked up to Wales to find its highest mountain clad in a coat of winter snow. Ill-equipped and with zero experience they followed two men with ice axes up the Pyg Track because they looked like they knew what they were doing. Halfway up all four were nearly avalanched, and when the two leaders turned around and headed down again, so did Chris and Anton.

Back at their hotel that evening, they overheard some people talking about rock climbing, an activity they didn’t even know existed. Anton had had enough, and hitch-hiked home the following day, never to set foot on a mountain again, but for Chris it was the most enjoyable thing he’d ever done in his life. He joined a rock climbing group at Harrison Rocks, a sandstone crag in the countryside near London, and … well, let’s just say he turned out to be quite good at it.

Fast forward a few years, and Chris had joined the army and was posted somewhere on mainland Europe when he decided to slip away to the Alps for a climb. He wrote to a climber he knew to see if he could recommend a route. Although he didn’t say so, we can assume at this point Chris must have developed a little as a climber and acquired something of a reputation, because the climber he wrote to turned out to be the Scottish winter mountaineering legend Hamish MacInnes, who invited Chris to join him on a climb of, yes, the North Face of the Eiger.

Although he eventually became the first Briton to climb Europe’s best-known vertical graveyard, at this stage in his career the North Face of the Eiger was a little beyond him, and he knew it. In some trepidation he followed MacInnes up to the bottom of the face, and was relieved when thunder clouds appeared overhead. Glad to have an excuse to back out, he scrambled back down again with MacInnes cursing away behind him. Cowardly as this may seem (for anyone who doesn’t know about the Eiger), it obviously didn’t disappoint MacInnes too much, for the following year the pair were back the Alps as a rope team again, this time to have a go at a new route on the Southwest Pillar of the Aiguille du Dru. Here they bumped into another climbing legend, the maverick hard-drinking Lancastrian Don Whillans, who according to Chris dragged the whole team up after a falling rock struck MacInnes on the head and gave him concussion.

It was 1960, and by now Chris had enough of a reputation to be invited on a couple of army expeditions to the Himalayas. Cue some amazing photos of Kathmandu in an era which no longer exists, with only two hotels and none of the internet cafes, souvenir shops and bars of downtown Thamel. Back then there was only one road in Nepal and the team had to trek to Annapurna from Kathmandu. He showed another photo of the route he took up Annapurna II, up and over Annapurna IV and along a 2km ridge well above 7000m. It was the first ever ascent of the world’s 17th highest mountain, only a few metres short of the magic 8000m. He then resigned from the army to join another expedition to Nepal. This time he made the first ascent of Nuptse in the Khumbu region with a team of climbers who didn’t get along. They had a punch up halfway up, but completed the climb anyway. He showed us a picture of the Southwest Face of Everest, looking across the Western Cwm from the summit of Nuptse, and said at that stage in his life he harboured no ambitions of climbing it. I believed him, even if nobody else in the theatre did. The first ascent of Everest’s Southwest Face was arguably the crowning achievement of his life, but that was to come in the second half of the show.

The following year he did some more climbs in the Alps with Whillans (cut to a photo shot vertically up the Central Pillar of Freney on Mont Blanc, where some giant overhangs look like a few ledges on a smooth horizontal surface of rock). Then he started a new job at Unilever intending to, as he put it “join the corporate world and sell margarine for the rest of my life”.

It didn’t quite turn out that way. A few months into his new job, Whillans phoned him up and asked if he wanted to join an expedition to climb the Central Tower of the Torres del Paine, a massive vertical spire in Chilean Patagonia. He couldn’t resist but was disappointed when his employer wouldn’t let him have the time off work, so he ended up resigning again. Luckily he had a few more months in the Alps before joining Whillans’ expedition to the Andes. He made a complete traverse of the Grandes Jorasses in France with Ian Clough, and feeling in good shape the pair nipped over to Switzerland to make the first British ascent of the North Face of the Eiger. This brought him recognition at last, and enough media attention to begin forging his career as a professional mountaineer.

Onwards to South America. Chris, Whillans and their companions were camped beneath the Central Tower of the Torres del Paine intending to make the first ascent, when an Italian team appeared claiming to have the only permit to climb it. The forthright, hard-drinking Whillans wasn’t known for his international diplomacy, and at this point in the presentation Chris introduced an audio clip of somebody reading from Whillans’ diary in his dry northern drawl.

“Permit or no permit, we told the Italians one thing was certain. We were camped at the foot of the tower, and the only way we were going to be moved away from it was by force.”

The next part of the show did little to advance Anglo-Roman relations, but appealed to members of the audience with a liking for light-hearted international competition. He showed us a few slides of the British team carrying planks of wood across boulders to erect a makeshift hut below the tower which couldn’t be easily removed by their European brethren. The structure was completed with a door bearing a legend scribbled in chalk: Hotel Britanico. As soon as there was a break in the weather, Chris and Whillans awoke early, sneaked past the Italian camp and nipped up the Central Tower while their rivals were still getting dressed. The precise details of how the pair climbed this frightening vertical pillar of rock weren’t discussed, but Chris evidently felt we’d prefer to see a photo of the British team opening a bottle of celebratory champagne back at the hut, another staggeringly bold first ascent accomplished.

At this point in the show I was becoming a bit mountained out. We had seen mountain after mountain, vertical rock face after vertical rock face, and Chris had described them in such a matter-of-fact way he could have been taking us through a few village cricket matches he had played in his youth, complete with their cream teas and cucumber sandwiches. But I’ve been to a few of these places. I’ve looked up the Nuptse Ridge from the south and across to Annapurna II from the Kang La above the Annapurna Circuit. I’ve even stood below the Torres del Paine, and although it was tipping down while I was there and I could see bugger all, I can almost imagine how horrendous it would be to climb if I close my eyes and try to picture the most frightening thing I can think of.

These were extreme ascents we were talking, and I was slightly overwhelmed. It was a good time for Chris to pack us off for the interval. The bar at G Live in Guildford serves real ale, and it’s one of those civilised places where they don’t mind you taking your drinks back into the theatre during the show. We discussed the first half, and I was inevitably asked whether I was inspired to have a go at any of Chris’s routes myself. I would rather tight-rope walk across the Niagara Falls with my genitals attached to a crocodile, but my respect for Sir Chris and his achievements has no bounds.

The second half of the show covered Chris’s most iconic climbs. He was now at the stage in his career when he was able to attract large amounts of corporate sponsorship to organise big Himalayan expeditions, and received national television and media coverage mountaineers can only dream of today. He became Britain’s most famous mountaineer, and no modern equivalent is ever likely to become a household name like he was back in the 1970s and 80s.

He resumed after the interval with the first ascent of the South Face of Annapurna, nearly 4000m of vertical rock, ice and snow, most trekkers get an awe-inspiring view of from the Annapurna Sanctuary. The Swiss superstar Ueli Steck completed a solo ascent of it only last week, but back in 1970 nobody (with the possible exception of Reinhold Messner) would consider such an intimidating climb any other way than expedition-style. This involved multiple climbers load-carrying up and down the mountain, gradually establishing higher camps in preparation for a summit pair to make a summit dash and reach the top.

Chris’s two lead climbers were Don Whillans and Dougal Haston, and he described their contrasting qualities: the old stager, no longer at his peak, slightly portly but oozing with confidence and the wisdom of years, and the young student, fit, bold, confident and brash, keen to push the limits but on his first Himalayan expedition and needing an experienced hand to mentor him. He mixed his photos with two pieces of interesting video footage. The first was Whillans and Haston discussing their motives for climbing as they leaned against a rock at base camp.

“I think we have very different reasons for climbing,” said Whillans in his slow northern drone. “Me, I have a very practical approach to climbing. I’m a craftsman. As I make my way up a route I feel like I’m a blacksmith at an anvil, shaping his tool. Dougal I think has a more romantic approach to climbing.”

“I don’t agree that I’m romantic,” says Haston in his gentle Scottish burr. “I’m more analytical. When I’m climbing a route I feel like I’m solving a problem.”

Equally enlightening is footage of Mick Burke carrying a heavy load up steep rock. He narrates the film himself, describing the process of climbing slowly at high altitude.

“At some stage you believe you’re too exhausted to carry on. Then you take another step up and you realise you’re not too exhausted. You can take another step, and another. It’s your mind that’s exhausted, not your body. You realise you’re alone, miles from anywhere and nobody is going to help you. Only you can get yourself up the mountain. It’s knowing this that makes you think you’re too tired to carry on.”

Next came Chris’s two attempts on the Southwest Face of Everest, the first too late in the season and up a line which they realised was a dead end. The second in 1975 was successful; not only was it a new route on Everest but Haston and Doug Scott became the first Britons to climb it, on an epic push which required an overnight bivouac close to the South Summit. He showed some more video footage, this time of him with a giant satellite phone the size of a chamber pot clamped to his ear, while he spoke to Scott at Camp 6 after returning from the summit.

“Well done, jolly good show and congratulations. We’re all very proud of you,” he says calmly, before putting the phone down and bursting into tears.

His first ascent of Baintha Brakk in the Pakistan Karakoram, otherwise known as The Ogre, with Doug Scott in 1977, is skipped over very quickly. It was an epic descent where everything that could go wrong did, except they all survived. Scott broke both legs just below the summit and spent several days crawling back down. One detail from this part of the presentation stuck in my mind. Chris showed a photo of the team swimming naked in a rock pool during the trek in, followed by a photo of a Balti porter holding his hands 12 inches apart as though describing a fish he’s just caught.

“This is one of them describing what he’s seen,” said Chris.

I roared with laughter, even though I knew exactly what he was going to say before he said it. Earlier this year I saw Doug Scott give a presentation called A Crawl Down the Ogre, during which he showed the same photo and made the same joke. I realised Britain’s two most distinguished mountaineers must have been touring for years showing this photo and making the same knob gag to audiences up and down the country.

But there was a darker note to the story here as well. The Ogre climb turned out well in the end, but while most of Chris’s expeditions during this period were achieving their goal, they were also resulting in at least one fatality. He didn’t skip over these accidents, and paid tribute to all of the climbers who had lost their lives: Ian Clough in an avalanche on Annapurna, Mick Burke who went missing on Everest, Nick Estcourt in an avalanche on K2, and perhaps most notoriously Pete Boardman and Joe Tasker, who were last seen climbing The Pinnacles on Everest’s Northeast Ridge.

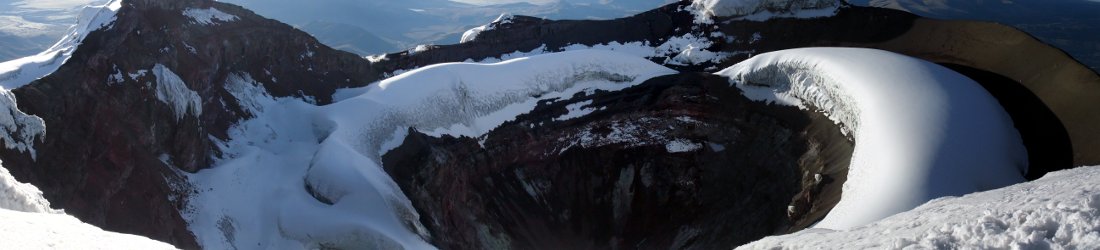

His career was starting to wind down in the 1980s. He completed the first ascent of Kongur in the Chinese Pamirs, and showed us photos of a horrendous knife edge corniced ridge on the West Summit of Shivling in India, another first ascent he made with Jim Fotheringham, but thereafter his climbs became less extreme. He finally reached the summit of Everest himself in 1985, by the standard route along the Southeast Ridge with a Norwegian team.

“Everest gets slagged horribly these days,” he said, “but it’s a fantastic route, if only it didn’t have so many people. Back then we had it to ourselves and it was marvellous.”

In 1991 the sailor Robin Knox-Johnstone agreed to sail Chris to Greenland on condition he got him up a mountain. Their aim was to climb a peak called Cathedral.

“But I’m most horribly embarrassed,” said Chris. “Our maps weren’t very good and we ended up climbing the wrong mountain. And we failed to reach the summit, but it was one of the most enjoyable expeditions I’ve been on, which just goes to show you don’t have to reach the summit to have a good time.”

He explained how he was very competitive in his younger days, but as he grew older and gradually realised he could no longer compete, he became more relaxed about his climbing and enjoyed it more.

Last year he was asked to carry the Olympic torch to the summit of Snowdon. They took the train up and we were shown a photo of Chris clad in white holding the torch aloft. His life had come full circle. He had begun his presentation by showing us a snow-dusted Snowdon he had tried to climb as a 16 year old, a trip that kindled his interest in the mountains.

He had one last photograph to show us, an aerial view of a Himalayan panorama taken from an aircraft. Miles and miles of snow-capped mountains stretched to the far horizon.

“There are no doubt some of you out there who want to climb Everest. I say this to you. Don’t climb Everest. It’s horrible; you’ll be climbing it with 400 other people. There are 100s and 100s of unclimbed mountains out there. Climb one of those. That’s a real adventure.”

I imagine if you’ve done what Sir Chris has done, climbing Everest by the standard route must be horrible, and pretty mundane to boot. For mere mortals it’s a different story. When I climbed Everest I didn’t think it was horrible; I thought it was amazing.

But he’s right about the last part. Sometimes we’re a bit too obsessed with the famous mountains. We should go out and explore a little as well.

But wow – what an extraordinary life! What was the score in the match between England and Montenegro? I didn’t care. I’d just been on a privileged roller-coaster ride, a celebration of some of the world’s great climbs with a man you should really try and see while he’s still lively enough to share his enthusiasm for them.

What an amazing life, and what a presentation! You are right, he’s almost done too many things for one single presentation… Very inspirational!

What do you think about Ueli Steck’s recent Annapurna ascent?

If I thought Ueli was superhuman before, he’s just gone up another level. He’s the new Messner.

https://www.markhorrell.com/blog/2012/ueli-stecks-ridiculous-mountaineering-career/

His ascent last week in no way undermines the achievements of Sir Chris’s team in 1970, though. It was a different era then, and in every era someone breaks new ground.

What a great evening you must have had wish I could have been there Cheers Kate

Annapurna is a beautiful mountain as Alan Arnett’s fast time photography of Ueli ‘s recent ascent reminded us. Sad memories for me as I lost close friend Ian Clough to an avalanche as he returned from his successful summit. It reminds us how expeditions have changed in format since the fifties. Ueli’s climb would have been quite mind boggling then and still is in many ways even today, quite beautiful. Cheers Kate

Sorry to hear you were friends with Ian Clough, Kate. Sir Chris paid tribute to him during the talk and described the incident in detail.

It was virtually the final act of the entire expedition, and happened as they were clearing the mountain after Whillans’ and Haston’s successful summit. There was an area of seracs at the bottom of the route which they knew was going to collapse sometime, but they weighed the risks and considered it very unlikely to happen during the short instances when they were crossing underneath.

He was returning from the very last load carry with one of the other climbers, Mike Thompson, when it happened. Thompson was able to dive against the wall and gain some protection from the huge blocks of ice which fell from the serac, but Ian Clough was right in their path and had no chance.

A tragic end. I know it doesn’t make it any easier, but I guess he would have been aware of the risks and accepted them.

It was great to hear Sir Chris made a mention of Ian and that he is still in the minds of folk today. As you will be aware we were only young at the time and it came as a big blow to young minds. Unbelievably our next door neighbour who was a member of Durham University climbing club was killed in Corsica in the same year. The police came to our house to ask for support when they went to see his mum with the news. Shortly before I had a close encounter in the Cairngorms which ended by me saving someone’s life.We all came from the same small town in Yorkshire so as you can imagine it was quite big news.There was a new Function Hall and Library being built in Baildon at the time of Ian’s death and on completion it was named after him. It stands in the centre of the village still and is very much in use to this day. Sadly, which is quite normal, the name doesn’t mean anything to the youngsters and the new comers to the village today but it is always uppermost to his peers. He was such a lovely unassuming guy and we were all very proud of him. Cheers Kate

Sounds like you have some great memories there, Kate. Thanks for sharing.