No, the title of this post is not a euphemism, but a reference to the similarities between one of the great mountaineering survival stories, Joe Simpson’s Touching the Void, and another less well-known survival story which happened in the Pakistan Karakoram in 1977.

For the second weekend in a row I found myself at a trade show evading all the sales executives trying to sell me holidays and equipment, and heading straight to one of the lecture theatres to hear a talk. I was at the Adventure Travel Show at London Olympia to see Doug Scott’s talk entitled A Crawl Down the Ogre.

Doug Scott, as many of you will know, is one of Britain’s all-time great high altitude mountaineers. He was the first Briton to climb Everest along with Dougal Haston in 1975, by a new route up the Southwest Face. He also made the third ascent of the world’s third highest mountain Kangchenjunga in 1979, again by a new route. He was known for his outstanding physical strength and stamina, and nothing exemplifies this better than the first ascent of 7285m Baintha Brakk, better known as The Ogre, with Chris Bonington in 1977, which became a struggle for survival when he broke both of his legs on the way down.

Many people are familiar with Joe Simpson’s story Touching the Void, about when he broke his leg close to the summit of 6344m Siula Grande in Peru, fell into a crevasse on the way down, was left for dead by his climbing partner, and crawled along a glacier for three days to reach safety. His book about the climb was a bestseller and was made into an award winning film. It has now become a standard text for GCSE English pupils, although not all teenagers are fans of the book, and some of them went as far as tweeting him abuse after their exams last year. One student even described him as a “crevasse wanker”. While this may seem harsh on Joe, as he didn’t choose to fall down the crevasse and it’s unlikely he cracked one off while he was down there, it’s possible for me to understand the teenagers as well. Had D.H. Lawrence been on Twitter when I did my ‘A’ Levels, I may well have reacted in the same way (though in my defence Touching the Void is a million times more exciting than Sons and Lovers).

Less well-known by people outside the climbing community is Doug Scott’s story, which is similarly epic, has much in common, but also many differences. Leaving aside the survival aspect, the adventurous spirit needed just to reach the foot of a remote mountain is common to both stories. Doug described how he and his five companions caught an Afghan Air flight to Kabul, then hitch-hiked over the Khyber Pass into Pakistan, where they had to recruit porters for the trek in. He described how the people of Baltistan in Northwest Pakistan were becoming accustomed to mountaineering expeditions, but still lived in great simplicity and were only just learning about the ways of western travellers. The American Jim Whittaker had experienced porter strikes the previous year and had resorted to burning 100 dollar bills in front of them in order to convince them wages weren’t negotiable. Doug’s team didn’t have that sort of money available, so they decided to recruit porters with disabilities who wouldn’t normally be able to get employment, in the hope they would be more loyal to the team. Their standards of hygiene were very different from westerners, and in an early part of the trek the six mountaineers stripped off and jumped into a pool to get clean while their porters looked on in astonishment.

“Here’s one of them describing what he’s seen,” said Doug, cutting to a photograph of a Balti porter making the sort of gesture you might expect an angler to make after catching an 18 inch salmon.

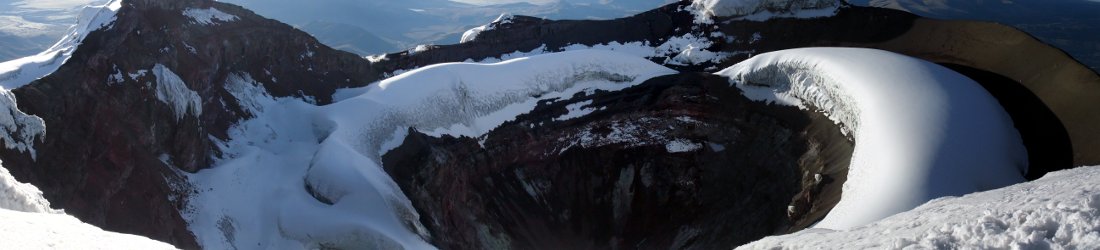

The presentation was sprinkled with photograph after photograph of dramatic Karakoram scenery, very different from other parts of the Himalayas. The area contains four of the world’s largest glaciers outside the polar regions, but many of the mountains manifest themselves as giant vertical walls of cracked and jagged rock, so steep that their surfaces are largely free from ice. It’s a rock climber’s playground, but at such an extreme altitude it contains hazards not found elsewhere in the world.

The climb itself fell into two distinct phases. Doug and another climber, Paul ‘Tut’ Braithwaite wanted to have a go at the South Pillar, a huge 1000m vertical cliff of granite, while the other four climbers, Chris Bonington, Nick Estcourt, Clive Rowland, and Mo Anthoine concentrated on the Southwest Flank, which contained an easier route up ridges and snowfields, but was still quite severe. Doug didn’t get very far up the South Pillar before having to abort the climb because Tut was injured by a falling rock, but the others established a high camp at 6100m before Chris and Nick took five days of food and got all the way up to the Ogre’s West Summit in one rapid push. They regrouped back at base camp, and Nick and Tut decided to rest there while the other four climbers had another go at the main summit.

All four made it to the West Summit for a second time, which was snow lined and more straightforward, and established a snow cave at 7000m on the ridge connecting it to the main summit, which would be their high camp. Doug and Chris then had a go at the main summit, a 250m rock pinnacle which required many pitches of extreme rock climbing (Doug said it was difficult to estimate the climbing grade because the problems are very different at high altitude, but he said it was certainly the most technical climbing he ever did at that altitude). They reached the summit on July 13th as the sun was setting. Because it was so late in the day they knew they had to get down quickly while there was still some daylight, which they did by abseiling. During one pitch Doug took a 30m pendulum swing against a rock face and smashed his legs. He pushed off with one of them against the rock, and felt such unspeakable pain wrench through him that he realised it must be broken. He pushed off with the other leg, and felt the pain again. Both legs were broken, and they were on a small ledge a little below the summit, with more than 2000 metres of extreme climbing ahead of them if Doug was to get back to base camp safely.

“There wasn’t any fear, just anticipation,” said Doug. “I never had any doubt that I would get down, I just didn’t know how I was going to do it.”

This contrasted with Joe Simpson, whose first instinct after realising he’d broken his leg in an extreme location, was that he was a dead man. Doug likened the problem to any other large project. To avoid becoming disheartened by the distance they still had to descend to safety, he set his sights on the next few hundred metres ahead of him and just concentrated on that.

Luckily for Doug (did I really say that?), he had only broken his lower legs, which meant he was able to abseil. Abseiling involves a climber leaning back on the rope and walking down the face backwards by pushing off with their feet. With his broken legs Doug couldn’t do that, but presumably he was able to improvise an alternative method using his knees. By contrast Joe Simpson smashed his tibia (lower leg bone) up into his knee joint, smashing the knee as well. This meant he was unable to abseil and had to be lowered by his partner Simon Yates. Even so, both climbers will have been in considerable pain. While Joe Simpson vividly described the agony he felt having his legs smashed around as he was being lowered, Doug described his descent with Chris Bonington very matter-of-factly, almost as though it was straightforward.

They didn’t get very far that day, and had to bivouac on a ledge a long way up the steep rock section.

“The advantage of bivvying in the open like that is that you don’t have to pack away in the morning. You just get up and leave,” said Doug, somehow managing to find a positive from their precarious situation.

The following day they reached the snow cave where Clive and Mo were waiting for them, and spent the night there, sharing their last freeze dried meal. They still had to climb back up over the West Summit before they could go down, but on the third day a blizzard was howling, so they spent a second night in the snow cave. By now Doug was quite literally crawling down the mountain on all fours, something he again describes as though it’s quite easy.

“It was no problem because I’d only broken both tibia,” he said. “If I’d broken my femur [upper leg] then I’ve no doubt I’d still be on the mountain.”

Again the contrast with the agonising three day crawl described in Touching the Void is marked, but before anyone accuses me of suggesting Joe Simpson’s a pansy (which I’m not), it’s worth pointing out another of the more obvious differences between the two stories. Touching the Void is as much about the sense of being alone and left for dead as it is the struggle for survival. By contrast Doug had help from his companions at every stage, first Chris Bonington, and then Clive Rowland and Mo Anthoine, who took over cutting steps and fixing ropes for the abseiling once they were back in high camp.

The descent to base camp took seven days in all, almost all of it in bad weather through fresh snow. Chris became a casualty too when he took a fall and broke two ribs. He panicked later that day when he coughed his lungs up in one of the tents. He thought he had pulmonary edema and would die if he did not descend immediately.

“Don’t worry, Chris,” said Doug, trying to reassure him, “you’ve probably only got pneumonia.”

Doug became accustomed to crawling and said he even found it easier in the thick snow. The others sometimes sent him ahead to break trail. The hardest part was the final section between advanced base and base camp, four miles on rocky moraine, rather than the soft snow he’d been crawling on until then. He wore through four layers of clothing and his knees were swollen and bleeding.

Mo arrived at base camp first and found a note from Nick and Tut saying they had left that morning. After seven days of waiting they assumed everyone must be dead. Mo then set off at a run to try and catch up with them before they reached civilisation and reported the news back to friends and family. When Doug, Chris and Clive arrived they found another note from Mo to say he’d gone after them.

It took another five days for relief to arrive, which they had to spend living on a diet of Tom and Jerry nougat bars, the only supplies remaining. It took twelve Balti porters three days to evacuate Doug down the Biafo Glacier on a makeshift stretcher made from a sleeping mat and juniper poles to a place where it was safe for a helicopter to land. He remembered the porter who had carried a 30kg load including 31 eggs for twelve miles over the impossible terrain of the Biafo Glacier to base camp without breaking a single one, and he knew they would get him back safely. He had nothing but admiration for them as he waited, helpless to assist. They had no leader and made all their decisions about his safety collectively. By contrast the helicopter flight was less gentle. As they were coming into Skardu the engine cut out, and they had a six metre crash landing. Fortunately nobody was injured, but the chopper was trashed and Chris had to wait many more days with his broken ribs before a replacement could be sent.

Doug described his ordeal in such simple terms that you would think he assumed everyone in the audience would have behaved in the same way in those circumstances. While it’s amazing what the human body is capable of in extreme conditions, even so he must have been as hard as nails. In fact most of us would have curled up and died long before reaching base camp, and that’s what makes stories like Doug’s and Joe’s so special. There aren’t very many of them, while there are many more which end in tragedy.

After the talk I went for a pint in a nice warm pub with comfy seating.

Doug’s complete account of the adventure is available online at the Himalayan Journal website, and prints of his incredible photographs are available from Doug Scott’s website.

What a brave, heart wrenching story.It has had little publicity and it is the first time I have had the opportunity to read the account. I have read much about Doug Scott and his expeditions but unbelievably knew nothing about his freak accident on The Ogre. The admiration I had for him in the past has shot up out of reach and when I again hear or read his name it will be written in gold. Brilliant effort Doug and thank you Mark for putting it fittingly in the spotlight. Cheers Kate

Thanks, Kate. He doesn’t seem to have written much about his climbs, and perhaps they sometimes get forgotten about. They were hardcore in those days. 😉

Dear Mark, Ozone is very toxic, is found at high altitudes and is more dangerous than phosgene. It is obvious that Chris, who was coughing up his lungs, had suffered the effects of ozone toxicity. It causes small blisters in the lungs and oedema. He was right to want to descend immediately as ozone is probably fatal to humans exposed to 50ppm for just one hour. Do you know if any mountaineers have measured 03 levels on Everest? Thank you very much for your superb article. I hope Chris has completely recovered. Kind regards Diana Hughes

Sorry, I was too slow to add the notification. Diana

Hi Diana,

I’ve not heard of mountaineers suffering from ozone toxicity before, and it’s never been mentioned in any of the lectures or articles I’ve attended or read about altitude sickness. That’s not to say it doesn’t happen. I’m not a doctor so don’t know enough about it to comment.

There is a team of doctors on Everest at the moment conducting various tests into the effects of high altitude on the human body, but there’s no mention of testing for ozone levels on their website:

http://www.xtreme-everest.co.uk/overview

I expect Sir Chris has recovered from his coughing fit now. 😉

Regards,

Mark.

Dear Mark, Thank you for the xtreme-everest website info. I will follow it up. When oxygen is thin at high altitudes the UV light breaks the oxygen bonds which then reform as triatomic oxygen or ozone. I believe that altitude sickness is partly the toxic effects of ozone in the lungs. Ozone is also produced as a by-product of photoluminescence, sparking electrical machinery, printers and air conditioning units plus many other sources. Regards Diana

Interesting stuff – the high altitude docs seem to have missed that one!

Pingback:10 Epic Tales Of Survival Against All Odds | ratermob

Pingback:Survival Against All Odds | Michigan Standard

Pingback:Fred - Gerg's Net

Came across this page by serendipity. I remember seeing slides of this incidence during Doug Scott’s talk of his climbing endeavors. Pictures showed the rock face and the swing that broke his legs, his walk on fours, sorry shape of his knees at the end etc. We were truly awed by this story and his other exploits.

This was in late 80’s. In Mumbai. Talk was organized by Harish Kapadia

Pingback:Pakistan launches helicopter search for US climbers missing on Ogre II | danilnews

I remember being at a lecture by Doug Scott in Wigan in the late 70s. I think it was about his descent of the Ogre with two broken legs. As he started talking, I realized that I couldn’t see his slides because he was standing in front of the screen. So I asked him to move a little bit so that I could see. He said to me, “move along the row”. I replied, “I have paid £5 for this, so you move,” He said OK and moved. Afterwards, I spent a couple of hours in a pub with Doug and Joe Tasker, who later died on Everest, hanging on every word they said. RIP Doug Scott.

You’re a brave man, Patrick! And very lucky. Nice anecdote.