Tweet about tourism in Tibet and within minutes you are likely to find yourself on the receiving end of hate tweets from Free Tibet enthusiasts bombarding you with photos of Chinese soldiers parading in front of the Potala Palace. How effective these Twitter accounts are at moving Tibetans closer to independence I don’t know, but with the report spam button only two clicks away my guess is not very. Equally curiously, I once remember having a conversation with a member of the bar staff in a London pub who was wearing a Free Tibet tee-shirt, and being surprised to discover he had never been there.

Tibet has always been a place to arouse strong passions, for reasons which aren’t always obvious. In the 19th century it was the focal point for much intrigue between Russia and Britain as their respective empires tussled for territory in Central Asia. Its inaccessible location at an obscene altitude, and guarded by deserts and mountains, meant virtually nothing was known about it outside its borders. In a period of about 15 years towards the end of the 19th century it was the subject of an informal race by explorers of many nationalities to be the first to reach its secret capital Lhasa, a race that eventually required a highly disciplined army equipped with modern weapons to win.

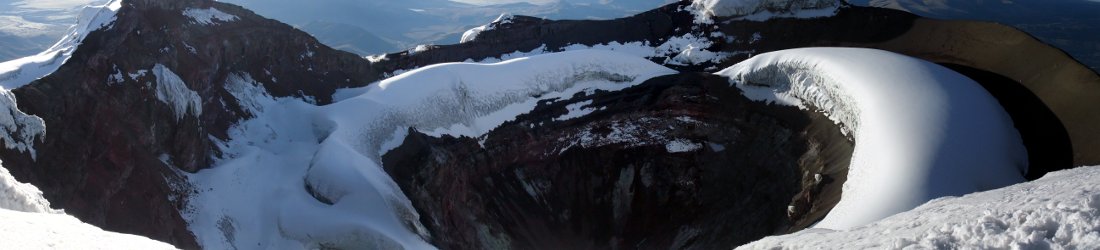

I’ll try not to delve into Tibetan politics in this post, because they’re complicated, and I’ve discovered the more I learn about this once-forbidden land of warrior monks, the less I understand. I’ve travelled there three times on mountaineering expeditions and it intrigues me too, which is why I was keen to read Race to Tibet, a new historical novel by indie author Sophie Schiller.

The novel is based on the true story of Gabriel Bonvalot, a French explorer who joined the race to Lhasa in 1889-90, and made a winter crossing of the Tibetan plateau with Prince Henri of Orleans and a Belgian missionary called Father Dedekend.

I’ve covered historical fiction once before in this blog, and it didn’t have a happy outcome. Jeffrey Archer’s novel Paths of Glory, about George Mallory, does for historical accuracy what The X Factor does for music. I was relieved when I saw a substantial bibliography and historical notes at the back of Sophie’s book. Although I’m nowhere near as familiar with Bonvalot’s story as I am with Mallory’s, I’m fairly confident she has done a much better job at keeping in touch with reality than Lord Archer did with Mallory and his magic travelator.

Bonvalot’s journey across Tibet was no fairytale adventure. He chose to enter by the hardest and longest route from the north. This involved crossing the Altyn Tagh mountains and the desolate high-altitude plateau of Chang Tang, and like Last of the Mohicans, there was no minute of relief from the difficulties his party encountered along the way. At one point they travelled for 72 days without seeing another human being, constantly menaced by freezing conditions and the devastating winds of the Tibetan plateau. Frequently they struggled to find enough food to eat, and their health deteriorated. As they approached Lhasa they were harangued by horsemen and government officials determined to keep them from entering the holy city, and there was much treachery. Race to Tibet describes these struggles vividly, and gives a real sense of the hardships they endured.

I don’t want to give too much of the plot away, as you may be interested in reading the book yourself, but it charts a true story and is already fairly widely known. It also means Sophie has no control over the final outcome. While many writers and particularly film producers have been guilty of changing history to provide a more satisfactory ending, this is not one of those books, and is better for it. I remember going to see the film Nordwand at a cinema in Central London, about Hinterstoisser and Kurz’s attempt on the North Face of the Eiger. As I left the cinema many of the audience were horrified all the main characters ended up dead. Some of them thought the ending was a bit gratuitous, where a man gasped his last breath while dangling from a rope two metres away from his rescuers. I didn’t tell them I knew that was going to happen. But without being too much of a spoilsport, I’m happy to say Race to Tibet doesn’t end quite like that.

Where Sophie has used poetic license effectively is by filling her story with a colourful cast of supporting characters, not all of whom are based on real people. There is Camille Dancourt, the naive but determined wife who attaches herself to the expedition to search for her lost husband, Pema the Tibetan Princess who is making an illicit journey to rejoin her family in Lhasa, and Imatch the hot-tempered camel-driver. One of my favourite characters is the redoubtable caravan leader Rachmed, kind of a cross between Jeeves and Rambo, who has a habit of solving the party’s problems through reckless acts of single-handed bravery.

I enjoyed reading Race to Tibet. If I have one criticism then it could perhaps have done with one more review by an editor, as I spotted the occasional typo and awkward sentence, but IMHO this is a minor issue. Indie authors don’t have teams of editors helping them to polish a manuscript till it shines like a pair of patent leather shoes at a job interview, and we should all be happy we live in a world where quirky stories like this one can be published and find an audience. This is Sophie’s second novel, and I’m sure she will develop as a writer. I will certainly be looking out for more of her work.

If there are scenes in the novel which appear to stretch credibility, this is probably because Tibet itself can challenge belief. After finishing Race to Tibet I decided to re-read Peter Hopkirk’s Trespassers on the Roof of the World, a history book about the race for Lhasa. When Mark Twain said truth is stranger than fiction he could have been talking about this book. It’s full of weird true stories, like that of Henry Savage Landor, who was made to ride across the Tibetan plateau strapped to a spiked saddle while his captors took pot shots at him with matchlocks. Then there’s the Pundit’s servant Kintup, who escaped from slavery, chopped up 500 logs and threw them into the River Tsangpo hoping someone would see them downstream and solve the geography of the Brahmaputra; and perhaps most famously there is the Buddhist scholar Alexandra David-Neel, who claimed to see a monk levitating across a boulder field, and herself kept warm using the mysterious art of thumo reskiang, or self-heating. Great Game historian Peter Hopkirk died last year, and Sophie generously acknowledges his contribution to her research.

Like everywhere else Tibet has changed a lot in recent years. Whether you like it or not the country is now a part of China, and likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. But it’s still a weird and fascinating place, like nowhere else in the world. While some people believe by visiting Tibet you are showing support for the Chinese Communist Party, I firmly believe you help to preserve Tibetan culture by going there and learning more about it. I certainly hope to go back again.

These days travelling to Tibet is a little easier but far from simple, and subject to a series of impenetrable regulations imposed without warning by the Chinese government. In 2008 the north side of Everest was closed completely so they could carry the Olympic torch to the summit in secrecy. Protests in Lhasa meant the government didn’t issue tourist permits, and my expedition to Cho Oyu that year ended up being cancelled at the last minute. A similar thing happened to those intending to climb Cho Oyu in 2012.

At the time of writing it’s possible for an individual tourist to obtain a permit to travel to Lhasa, but only with a local operator, complete with tour guide, vehicle and driver. It’s necessary to pay a large deposit in advance to secure your permit, and don’t try entering wearing a Free Tibet tee-shirt, or carrying anything written by the Dalai Lama. They don’t let anyone from Norway in at all, because the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, which seems a bit childish. A good summary of current regulations can be found here.

But if you can’t go to Tibet then reading about it is a good substitute, and Race to Tibet is certainly worth a read. And this is probably a good time to point out that my three rather less surreal Tibetan journeys – to the North Col and summit of Everest, and to Cho Oyu – are available as e-books for less than the price of a packet of condoms.

Note: Sophie sent me a free copy of this book to review.

Thank you for your beautiful, thoughtful review! Well done. I love your description of Rachmed!

No worries, thank you! A good read.