We returned from a few days relaxation in the Amazon jungle earlier this week to learn that the Ecuadorian government was about to reopen Cotopaxi for climbing. This was exciting news for Edita, who is yet to climb it and keen to do so, but we had some strong reservations.

Cotopaxi (5897m), an active volcano that is Ecuador’s second highest mountain, has been closed for climbing since a major eruption in 2015. Now it seems certain that the first commercial clients in two years will be allowed to climb the mountain starting from tomorrow, 7 October.

But is the decision to reopen Cotopaxi the right one, or is it premature? Is the mountain safe again?

In this blog post I share my thoughts. My understanding of some of the issues is incomplete, and I’m happy to be corrected if anything here is incorrect. I am neither an expert vulcanologist, nor a medical professional familiar with the risks of sulphur dioxide poisoning. I write from the perspective of a commercial climber who climbed Cotopaxi in 2010 and would consider climbing it again if I considered it to be safe.

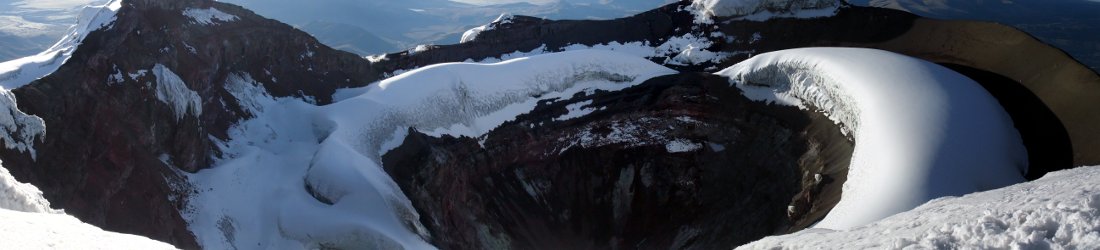

There is no doubt that a safe Cotopaxi, open for climbing again, would be a good thing. It is Ecuador’s most popular mountain, a perfect cone, visible from many locations in the central highlands. It is easily accessible, just three hours’ drive from Quito, with a car park at 4500m and a mountain hut at 4800m. It’s a good beginners’ peak for those wishing to learn the basics of glacier travel. It also has some amazing views from the summit, not least of which is the chance to look down into an impressive volcanic crater.

Mountain tourism in Ecuador has suffered since Cotopaxi’s closure. It was a good meeting place for guides to catch up and discuss routes and conditions on other mountains. Its nearest equivalent, Cayambe (5790m) has not proved anything like as popular. Cayambe shares nearly all of Cotopaxi’s merits as a glacier climb. It is only about half an hour further to drive from Quito, it is less steep and therefore marginally safer. It also has the additional significance of rising exactly on the Equator. It lacks Cotopaxi’s crater, but unfortunately it’s just not as famous, and this is perhaps equally important to peak baggers.

There has been talk of Cotopaxi reopening ever since we arrived in Ecuador a month ago. The manager of the refuge on its slopes was desperate for permits to be granted again. Although he still gets daytrippers walking up from the car park, it doesn’t match the income from climbers staying overnight.

Early in September we walked up to the refuge, and saw mattresses on the trail waiting to be carried up. We were able to look at the new accommodation, which has improved greatly since I stayed there in 2010. I remember a giant triple-decker bunk bed that could accommodate a dozen people, and creaked noisily every time somebody rolled over. Sleep was difficult, but now there are a number of dormitories, all with spacious double bunks (I could only count 50 beds, which may prove a problem on busy nights).

The following day I had cause to doubt the wisdom of reopening Cotopaxi just yet. We were driving to the starting point of our climb of nearby Sincholagua at 6.30am when we witnessed the release of a gas cloud from Cotopaxi’s crater. This was at just the hour when prospective climbers would be reaching the summit, and they would be standing right next to the explosion on the north side of the crater. While prevailing winds take the gas cloud southwest, away from climbers (as we could see from our vehicle), it would only take a sudden gust or change in the wind direction for climbers to be immersed in sulphur fumes.

This gas release we saw on the day we climbed Sincholagua was not an isolated incident. There have been other similar gas clouds in the weeks since we’ve been here.

Cotopaxi has a parallel with Popocatepetl (5452m) in Mexico. “El Popo” is Mexico’s second highest mountain, also an active volcano, a perfect picturesque cone, easily accessible from Mexico City. Mexico has many tourist treasures, and the Mexican government simply chose to close the mountain for many years. The gas fumes were considered too great a risk, and El Popo’s contribution to the tourist economy was not that significant.

I can understand why the Ecuadorian government and the tourist industry are keener to reopen Cotopaxi, so how dangerous is it, and what steps can be taken to lessen the risk and reassure tourists?

I don’t want to put the willies up anyone, but nor do I want to underplay the dangers of volcanic fumes. As it’s an unknown danger for most of us, I thought I would gather some data.

As I understand it, the main risk is from sulphur dioxide, a gas that in small quantities is considered safe, but in larger quantities reacts with the mucous membrane (that lines various internal organs) to form sulphurous acid.

It’s possible to smell sulphur dioxide in quantities as small as 0.3 to 1 ppm (parts per million) (source). This in itself isn’t dangerous – I could smell sulphur when I climbed Cotopaxi in 2010, and also from the crater of Kilimanjaro last Christmas – but how strong does that smell have to be in order to be considered dangerous? In fact, there are some established levels:

- 5 ppm – increased airway resistance

- 10 ppm – sneezing and coughing

- 20 ppm – bronchospasm (I don’t know what that is, but I don’t like the sound of it)

Adults can tolerate exposures of 50 to 100 ppm for up to an hour, but any more than that can lead to death from airway obstruction. I expect these figures may be less for climbers exerting themselves at high altitude, where oxygen levels are lower.

This sounds a little scary to me, and to make matters worse, it’s an unseen killer. Ecuador has many well-qualified mountain guides able to assess the risk of rockfall, avalanches and crevasse hazards, but none of them have any idea about safe levels of sulphur dioxide inhalation. As I understand it, this risk continues for some time afterwards, so a climber could potentially return safely to the refuge after a successful climb, unaware of the damage that has already been done to their lungs.

Perhaps the clouds we have seen emanating from Cotopaxi do not contain dangerous levels of sulphur dioxide. As a potential climber I would want to be reassured that emission levels were being monitored, at least for a transition period of some months after the mountain is reopened. If the level exceeds a certain threshold then the mountain should be closed, or guides asked to bring their clients down. I would also be reassured to see medical professionals at the refuge, checking up on climbers after they come down. Oxygen bottles at the refuge for those with breathing difficulties would help.

Those most at risk, however, are not tourists like me, who climb the mountain once and then go home, but the mountain guides who go up 10, 20, 50 times a year. They will be exposed to gas fumes for much longer periods, and could potentially experience long-term effects. Not all guides I have spoken to are comfortable about Cotopaxi opening again so soon. From next week they will be put under pressure to take clients up there or risk losing work. I wonder if any provisions are being put in place to monitor their long-term health.

We decided to climb Iliniza Sur instead, where the risk was merely a prolonged downpour, wet snow, and an early retreat from the hut at 4750m. Personally, I wouldn’t want to climb Cotopaxi just yet, with the gas clouds still releasing. If you’re thinking of climbing it too, then I would recommend a “wait and see” approach for now.

I can understand the government and tourism professionals wanting to open it for climbing sooner rather than later. I hope they take the necessary precautions, and keep my fingers crossed that all of those who choose to take the risk return safely.

I went to Machu Pichu the second day it opened after the earth quake. We ended up having to drive a couple of hours from Cisco which still had giant boulders coming down. We got dumped in a field for a pretty scary train as it was its maiden voyage and you could see the collapsed track. One you got to tow it was great. My view was and still is the trip was way to dangerous but the revenues to the government tend to trump safety a bit

Such a beautiful mountain, I’m sure you are familiar with Frederic Edwin Church’s magnificent paintings. If you haven’t done so already, do read the Von Humboldt biography. I’m sure you will come across many places and descriptions that are familiar.

Nice read, thanks 🙂

Thanks, Bob. I read the biography of Humboldt by Andrea Wulf while I was here in Ecuador, thanks to your recommendation. I enjoyed it. It’s a good tribute, though from my point of view the chapter on Chimborazo was a bit weak – there are quite a few inaccuracies and inconsistencies in Humboldt’s accounts of Chimborazo (eg. descriptions of altitude sickness, the height he reached, etc.), and it would have been nice to see these explored a little, rather than simply taken as fact.

Pingback:Is Cotopaxi now safe to climb? | No. Betteridge’s Law

Thank you so much. I was on the verge of booking a tour today at the tour agency and they talked about the sulphur level. I thought of this article and opted for a day trip to the refuge instead. I have been considering hard for the past few days and reading about the reopen of Cotopaxi summit and although a little disappointed, I’d rather not risk it.

Yes, good move, although an ascent of Cayambe would have been a great alternative.

Hi, I”ve only just found your article as I’m heading off to Ecuador next week to try to climb Cotopaxi. Any more updates on this? Thanks very much for this information.

Hi Samir, best to ask some climbing guides who have been up in the last few months. Are you climbing with an agency? You could try asking them. As I understand it, the crater is still emitting gas. If the feeling is that it’s still unsafe then Cayambe is a good alternative.

Glacier is in great conditions all the carveses are well covered with good bridges to pass, the service in the refuge is great and food is delicious, just back with an expeditions with Gulliver expeditions and my girlfriend,me and other 20 people have made it to the summit.Beautiful and impressive volcano… don’t miss it!