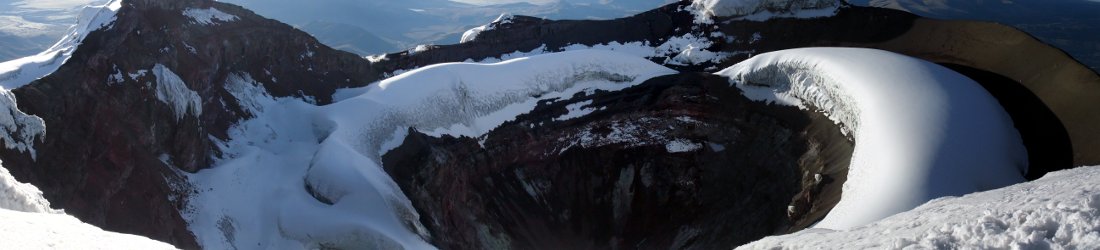

The crowning glory of Cotopaxi’s summit was not the 360° panorama of isolated volcanoes, but the gigantic crater directly below, a gaping chasm of chocolate-brown rock, framed by a shining ring of snow and ice. Mark Horrell, Feet and Wheels to Chimborazo

Yes, I know. I’m starting this blog post by quoting myself, but why not. In my latest book (published this year and available from all good retailers) I wrote a chapter about Cotopaxi (5,897m), the mountain some people describe as the highest active volcano in the world. In that chapter I talked extensively about its climbing history and its eruptions, as well as describing my own first ascent, so I think it’s well worth a read.

First climbed in 1872 by a vulcanologist, Wilhelm Reiss, his Colombian butler and a dog called Pedro, Cotopaxi’s proximity to Quito and ease of access has led to it becoming a popular peak for people wanting to sample a taste of mountaineering without having a full set of technical skills.

It’s possible to drive to a car park at 4,600m on the northern side of Cotopaxi. This has to rank as one of the most picturesque car parks in the world, overlooking the Limpiopungo Plain, ringed by the three disparate peaks of Ruminahui, Pasochoa and Sincholagua. From the car park it’s a stiff 200m hike on a scree-laden track to a hut, Jose Rivas Refuge, from where it’s possible to buy hot drinks and a meal and get a bed for the night.

I climbed Cotopaxi in 2010. For the most part, it’s an easy, if steep, glacier walk with some picturesque crevasses and ice formations, but what set it apart from other mountains, was its crater with a characteristic ring of ice around the rim. Alas, Cotopaxi erupted in 2015 and was closed for climbing for two years. It has now been re-opened, but people who have climbed it since have been disappointed to find the crater obscured by something. Whether this something is ordinary clouds or the gas still being emitted from the crater I wasn’t sure.

On the plus side, Jose Rivas Refuge, at the base of the climb, has been refurbished. In 2010 I had to share a monster triple-decker bunk with 20 other people. It appeared to be made from Meccano, and every time somebody rolled over the whole thing shook in a manner alarmingly like an earthquake (as well as erupting volcanoes, Ecuador experiences these frequently too). The new dormitories at Jose Rivas Refuge have spanking new double bunk beds with comfy mattresses that are altogether more pleasant to sleep on.

When the German scientist Alexander von Humboldt saw Cotopaxi in 1802, he described it as ‘the most beautiful and the most regular of all the colossal peaks of the upper Andes’. There are few more quintessentially conical volcanoes, and it’s hard to look at without wanting to climb it.

Although I had done so once before, Cotopaxi was the only one of Ecuador’s four big glaciated volcanoes (the others being Chimborazo, Cayambe and Antisana) that Edita hadn’t climbed. As soon as the mountain re-opened, she wanted to climb it at the first available opportunity, which meant our visit in October this year.

October is a relatively quiet period for mountaineering in Ecuador. There were only 7 clients and 4 guides at the hut that night, which meant plenty of space in the dormitory. I had a few good hours of sleep before being rudely awakened at 11.45pm by the staff of the refuge, who wandered through on their way to the kitchen and threw the lights on. They were keen to get everyone fed and on their way up the mountain so that they could go back to bed again.

I knew from experience that the climb isn’t a long one and the last thing we wanted to do was reach the summit before sunrise. So we had agreed with our guide Estalin Suarez to get up at midnight and leave at 1am. This meant that there was no real rush for us.

We left our sleeping bags and spare clothes on our beds and wandered downstairs for breakfast. It was a light affair, which was fine given that we’d had dinner not so long before: just bread, jam and copious quantities of coffee. The staff had closed up the kitchen and gone back to bed before we finished putting our boots on.

The walls of the dining room in Jose Rivas Refuge are lined with national flags that have been signed by climbers from their respective countries. A giant Union Jack already had 65 million signatures (which, coincidentally, is also the population of the United Kingdom). There wasn’t much space for me to add mine (or much point, for that matter). Although I toyed with the idea of plastering the phrase ‘Fuck Brexit’ across the whole damn lot, in the end I left it unsigned. But Edita was pleasantly surprised to find a much smaller Lithuanian flag with plenty of room for her to become only its second signatory.

Edita, Estalin and I were the last people to leave, on the dot of 1am and around fifteen to twenty minutes behind everyone else.

In many similar circumstances, I have found myself out in front before too long, but this didn’t happen today. It was the first time we had climbed with Estalin, and he had a different operating style. Despite joining an expedition to K2 a few years ago, he preferred to take things easy and enjoy the experience. Before setting off, he suggested that we start off very slowly so that we didn’t work up a sweat that would make us cold later on.

‘If we are doing well, then we can speed up later,’ he said.

He was true to his word, except that we never really speeded up. The lights above us, belonging to an Austrian couple, a lone Frenchman and their respective guides, remained ahead of us throughout the climb.

It was a clear night and although the ambient temperature was relatively warm, a biting wind lashed against us. For the first two hours we trudged slowly up zigzags of scree, stopping only once for a quick swig of water.

‘How is the pace,’ Estalin asked.

‘Too slow for Edita, but perfect for me,’ I replied.

For me, the temperature was about right. I had just three layers — thin fleece, PrimaLoft and Gore-Tex — on top, and two layers — thick trousers and overtrousers — below. I had only Thinsulate gloves with Gore-Tex shells on my hands, and this proved to be warm enough for most of the ascent. This meant that it was warmer than it felt. I often suffer from cold hands, and I’ve frequently needed down mitts at this altitude.

It took us about two hours to reach the glacier, where we stopped to put on crampons and rope together. Estalin led away with Edita in the middle and me at the back. Edita didn’t protest at this arrangement. The middle of the rope is probably the most annoying position because you have to ensure the rope is kept taut both in front and behind. You also have to keep stepping over it every time you change direction. But it also made sense for Edita to be there. She was quicker than me, so the rope would be more likely to loop if she walked behind. More importantly, she was also smaller, making it safer for everyone should either of us fall in a crevasse.

We slowly started ascending the glacier. The route went mainly to the right, spiralling around the volcano, but occasionally looping back again. There were several crevasses and snow bridges to cross. Estalin warned us when we reached these and we moved quickly over them. The ice formations were intricate and artistic but they were not places to linger.

For most of the time the wind was strong, but occasionally we passed a section where we were sheltered. It felt very cold indeed, but I was surprised to find that my fingers and toes were warm enough.

We continued the monotonous trudge in darkness. Occasionally we reached a safer spot and stopped for a drink. Edita was feeling colder than me, but she had a flask of hot tea in her bag which tasted like nectar.

At some point during the ascent we caught one of the other rope teams. They let us past but remained not far behind. At about 5am we reached the base of the Yanasacha Wall. This is a prominent landmark that can be seen from down below, where the rock of the mountain breaks through the ice of the glacier.

It was still dark, but it was going to be light very soon. I guessed that Estalin was going slowly so that we didn’t reach the summit before dawn. The Yanasacha Wall is at 5,700m. The coldest part of the morning, just before sunrise, was still to come. We stopped to put on our down jackets.

Until now, the route could have been the same one that I took ten years earlier, but now it changed significantly. The old route crossed to the north side, with a steep section over a snow buttress. Now we kept to the west side of the mountain, sticking to snow slopes on steepish zigzags.

There had been a mild smell of sulphur most of the way up, but now it became intense, almost overpowering. I wondered if prevailing winds were bringing fumes from the crater directly towards us. Twice I felt like I was choking and had to stop for a coughing fit.

Daylight crept up on us. Estalin had his GoPro clipped to a pocket and was triggering it with his voice.

‘Toma foto,’ he kept repeating as he stopped and looked down the rope at Edita and me coming up behind (it was a Spanish GoPro).

The sky was clear and we had a grand view of the Ilinizas close at hand. Iliniza Sur was heavily snow-capped. There was not a cloud to the north and we could see the three peaks of Pichincha standing proudly behind Pasochoa.

Having climbed it the previous week, I could now recognise the Mojanda massif by the twin peaks of Fuya Fuya on its western end. Behind Mojanda, Cotacachi nestled in a cloud pillow that made it resemble a line of snow-capped peaks.

The route wove a way between rock formations just below the summit crater. We reached the top at 7am after six hours of climbing. A vicious wind whipped clouds at rapid pace across the crater which I knew to be just below us. The crater was completely obscured for the whole time we were up there, but the speed of movement allowed occasional glimpses of the mountains to the south.

The wind made it feel colder than it was. The final rope team arrived on the summit just behind us, and turned to descend almost immediately. I was more inclined to linger. I knew that it wasn’t as cold as it felt, and every so often I caught a glimpse of the pyramid of Tungurahua between clouds. I waved my camera, desperately trying to get a sighting. We had climbed it three days earlier, but I’ve not yet managed to get a clear photo of it from a distance. But it was a hopeless task; it might just as well have tried putting out the volcano by pissing in it.

We stayed on the summit for just twenty minutes. Estalin was as keen to get photographs as I was, so we descended slowly. Cotopaxi cast its own shadow into the snowcap beneath us. We took many pictures of the intricate crevasses and ice formations that we had been unable to see in the dark. More dramatic than all of these was the island-like top of Antisana, rising above a sea of cloud to the north-east.

Below the glacier we could make a more direct descent down a soft bed of scree. I was too tired to run but could descend rapidly at an even walking pace.

We arrived back at the Jose Rivas Refuge at 9am. Six hours up and two hours down. The Swiss-Ecuadorian speed athlete Karl Egloff once did this journey in 1 hour 37 minutes. We weren’t quite up there with the best, but we were satisfied and still feeling strong.

Cotopaxi isn’t a difficult ascent, and these days you have to be lucky to see into the crater, but the wide views of isolated peaks still make it special, as do its fluted cliffs of ice. It’s now even possible to get a good night’s sleep. There are guides in Ecuador who have literally climbed it hundreds of times. Perhaps I will climb it again some day, but twice is enough for now.

My book Feet and Wheels to Chimborazo, about a unique climbing and cycling adventure in Ecuador, is available now in paperback and e-book format.

Thnx for posting – brings back good memories!

I´ve climbed the Pichinchas and Cotopaxi in 2015 (just before the eruption). On Chimborazo we had to turn back because of avalanche danger. I was back there this year to climb El Corazón and Chimborazo (finally made it!). After reading your Tungurahua report this volcano is on top of ecuadorian my to-do-list…

Greetings from Germany

Klaas

Nice description. I’ve enjoyed following your travels as your books were one of the first of this type that I encountered when I started going into the mountains. Funnily, I think we were on Cotopaxi within a few days of each other and I also went to Nevado San Francisco and Ojos del Salado from the Argentinean side at the end of 2019.

Looking forward to your next adventure. I’m off to Khan Tengri in July this year and my partner is getting annoyed that I seem to only focus on my big yearly objectives (the training alone requires that kind of focus, but also the fear of dying lol)