This is part 2 of a trio of posts describing a scrambling adventure in the Cuillin Hills on Scotland’s Isle of Skye. The first post described the eventful build up to our trip. This post describes the first day of our scramble and subsequent events.

But now we see our pedigree

Made plain as in a glass,

And when we grin we betray our kin

To the sires of the British Ass.

Alexander Nicolson, The British Ass

The following day we arrived at the southern end of Glen Brittle, where a campsite nestles beside the beach, looking across the sheltered bay of Loch Brittle towards the island of Canna.

On previous occasions I’ve found this campsite relatively quiet, with a handful of tents and the occasional solitary vehicle. Today it was filled to bursting with luxurious camper vans and not a tent to be seen, the consequence of quarantine rules and COVID-19 restrictions.

It was 7am. As forecast, the weather was fine and due to be rain-free for the next two days, and this had another consequence: we weren’t the only people attempting the infamous Cuillin Traverse.

At the car park, our guide Dave Fowler greeted another guide Caspar and his client Ross, who were also just departing for the full traverse. Ross was a big fella, and his pack was almost the same size. Had Caspar asked him to carry gold, frankincense and myrrh? I couldn’t contemplate scrambling along a knife-edge ridge with such a mass on my back, and I wondered why they hadn’t left an overnight cache at An Dorus like we had.

Dave told us that another guide from his agency West Coast Mountaineering had departed with his client at 4am this morning. They planned to traverse the whole ridge from Loch Coruisk, instead of doing the shortcut we were intending (see last week’s post).

We started out slowly along the well-worn track that crosses boggy moorland as it approaches the Black Cuillin from the west. To our right the sky was gradually lightening over the Atlantic as the islands of Soay and Rum came into view. There are a couple of river crossings here that had concerned me after the heavy rains of the previous week, but Dave had assured us that rain in the Cuillins washes off quickly. Sure enough, the crossings were quite easy.

We could see the sudden gap in the ridge that marked the peak of Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, and the twin summits of Sgurr Alasdair and Sgurr Sgumain rising above Coire Lagan to our left. This corrie was not our entrance into the Cuillins, as it is for many people. We were aiming for the next corrie around, Coir a’ Ghrunnda.

The trail began rising as we passed beneath Sron na Ciche, the southern ridge of Sgurr Alasdair. Here Dave told us about his speed wings accident last year. I’d never heard of speed wings, but apparently they’re nothing to do with fried chicken, and are some sort of cross between a paraglider and a parachute, which enable you to fly down but not up (some people might call this falling).

This time last year, Dave flew down a mountainous gully rather too quickly and landed in a crumpled heap. He waited in agony for hours while a police officer and then a mountain rescue team climbed up to help him, before a helicopter was summoned to carry him to hospital.

Several operations later, Dave crawled out of hospital and began the long road to recovery. Barely a year later, here he was guiding again. I wondered what he thought of me and my rather tame knee injury, and what dare-devilry he had planned for us here on the Cuillin Ridge. He was obviously a man who liked a spot of risk, but hopefully not too much.

But if my knee was listening to the story too, it wasn’t intending to cower in shame. A short while later the trail steepened and we began scrambling over the jumble of giant boulders that guards the entrance to Coir a’ Ghrunnda.

With each raise of my left leg, my knee squealed like a rusty harmonica. I gritted my teeth, but it was going to take more than that for it to perform like it’s supposed to. A hammer perhaps. I couldn’t physically bend the knee more than 90°, and this made stepping upwards an issue.

I devised a method of one-legged scrambling that involved putting my right leg forward and letting the left one trail behind — a climbers’ hobble. This wasn’t always possible though. There were some moves that demanded left foot first, and I knew it was going to be like this all along the ridge. I winced in pain. On one occasion I crested a boulder, looked up and saw Dave gazing back at me. He said nothing.

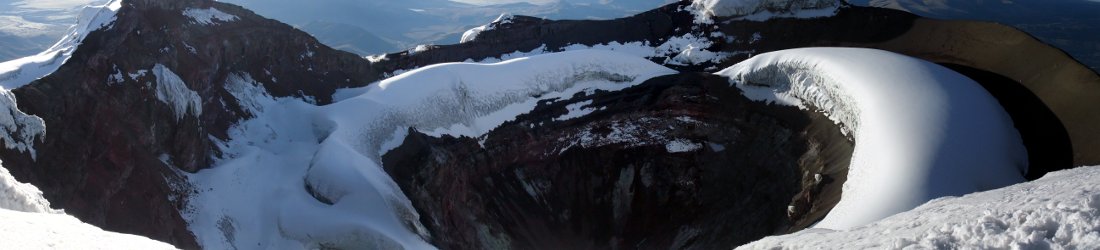

I dropped behind, but they waited for me beside Loch Coir a’ Ghrunnda, a silver lake that fills the corrie, surrounded by the tumbling rubble and jagged peaks of the Cuillin Ridge. Above us, the dark cliffs of Sgurr Alasdair, the highest peak on Skye, rose beneath a bright blue sky. It was a good day for going up, but from now on things were going to get harder. And Sgurr Alasdair was the first peak of many if we were going to reach our cache at An Dorus.

I had already accepted the inevitable on the way up the boulder field, but how was I going to break it to the others?

We stopped for a sandwich and I put down my pack.

‘Guys, I’ve got some bad news. There’s no way I’m going to complete the traverse.’

I looked at Edita. ‘But you’re strong. You carry on with Dave, but I need to descend while it’s still safe.’

‘Don’t stop here,’ Dave said.

‘Or I could go over Sgurr Alasdair and descend the Great Stone Chute,’ I replied.

‘That’s better.’

We descended the Great Stone Chute two years ago, a giant scree slope, the descent of which resembles the land-based equivalent of the watery TV game show Total Wipeout. Watching a hiker slide down the stone chute might be entertaining to spectators, but the descent wasn’t especially dangerous.

We sat in silence for a few moments. Dave made no attempt to change my mind. He probably expected this to happen as soon as I told him about my injuries. He explained that most clients who book the traverse don’t even start it. Of those who do, less than half finish. We were already in the top half just by setting off this morning.

Edita wasn’t happy.

‘I can’t believe it. If you’re not going to try then neither am I.’

Before I could reply, Dave came to the rescue.

‘If you’re up for it, I can take you over Sgurr Thearlaich and across the gap to Sgurr Mhic Choinnich. There’s a great section of ridge that not many people climb. Depending on how you’re feeling, we’ve still got Thursday and Friday to climb the other bits you haven’t done.’

This sounded like a great suggestion that could potentially salvage our trip. Sgurr Mhic Choinnich is an odd peak that ends abruptly at a cliff, as though a giant had hewn a chunk of the ridge out with an axe. Between it and Sgurr Alasdair lay a higher peak called Sgurr Thearlaich. Sgurr Thearlaich is only classed as a Munro Top; in other words, it’s over 3,000ft but it’s not a Munro. This means that hardly anyone ever climbs it. The section of ridge between Sgurr Alasdair and Sgurr Mhic Choinnich was therefore intriguing territory.

We climbed in zigzags up to the sheer wall of Sgurr Alasdair. To the right was an enormous cleft in the wall. We could see climbers making their way up the right-hand part of the wall. This seemed an odd choice of route, because it meant they would need to climb down into the cleft and back up the other side. Dave explained that this was the Thearlaich-Dubh (or T-D) Gap, a feature that is only climbed by purists who insist on scaling every feature on the ridge.

We kept to the left of the face, where a chimney led up Sgurr Alasdair. Dave belayed us up the chimney. We both struggled on this section, but above the chimney the scrambling was simpler — steep, but with plenty of hand- and footholds. We were able to climb most of it roped together.

Sgurr Alasdair is named after Alexander Nicolson (‘Alasdair’ being the Gaelic form of ‘Alexander’), a lawyer and writer who was known, among other things, for his poem The British Ass. This seemed appropriate for me, having felt a bit of one on the way up. Nicolson was born in Skye and made the first recorded ascent of its highest peak in 1873.

We reached the summit at 11.30. By now the weather had soured, and we found ourselves shrouded in a thin mist. We descended to a col, a short distance beneath the summit.

Here, briefly, the Cuillin Ridge became Skye’s answer to Clapham Junction. Climbers converged on all sides as we stopped for a snack: up the Great Stone Chute, from the top of the T-D Gap, and over the summit of Sgurr Alasdair like we had.

Dave knew every guide and greeted them warmly. Caspar and Ross caught up with us, having set off only a few minutes before us, and climbed the additional peak of Sgurr nan Eag while we were crawling up Coir a’ Ghrunnda.

I gazed at Ross’s giant pack. I was exhausted just looking at it. Had I tried lifting it down in the car park, I would probably have toppled over and fallen off. I couldn’t imagine carrying it along a knife-edge ridge. I would have needed lead boots to keep me on the trail.

Dave offered them our five litres of water stashed at An Dorus, since we would no longer be needing it.

‘It’s only a fiver a bottle,’ I quickly added.

Caspar looked at me darkly and Dave laughed.

‘Actually it’s Dave’s water,’ I said, ‘but he’s not a very good salesman.’

We descended about 20m, then followed a craggy 45º buttress up to the summit of Sgurr Thearlaich. The scrambling was fairly straightforward, but it was very exposed and was terrain I would have thought twice about had we not been roped to a guide.

A trio of unguided climbers appeared behind us. The one at the front looked like Joe Simpson, thought I could tell it wasn’t him, because the rope around his waist was still intact. He said they’d been intending to complete the traverse, but had bivied at Loch Coruisk last night and arisen so exhausted that they’d unanimously agreed to quit before even starting. They were now just learning this part of the route for another time. Dave gave them some tips.

From the top of Sgurr Thearlaich, the summit of Sgurr Alasdair was just a stone’s throw away. Had someone been up there, they could almost have reached across and passed us a sandwich. We were now deep in mist, and couldn’t see much of the route in front of us. The dark outline of Sgurr Mhic Choinnich was visible a few hundred metres away. Between us, the route slanted down slabs then passed to the right of a buttress on a narrow path.

We were on a dramatic balcony looking north-east to the Red Cuillin. Edita was so entranced that she dropped her water bottle. Before we had time to retrieve it, it had rolled down the slab and was winging its way down to Loch Coruisk. Not even Dave could fly fast enough to catch up with it. A short while later my camera nearly followed it. Luckily Edita noticed that the strap was broken and it was resting on a convenient fold in my jacket. I rescued it and put it in my pocket.

I was intrigued about how we were going to get up the black cliffs that guarded Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, and I was in for a pleasant surprise. Ahead of us lay one of the Cuillins’ hidden treasures, a magical passageway that turned a fearsome climb into an airy stroll.

From the gap between Sgurr Thearlaich and Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, a narrow ledge slanted upwards and worked its way around the western side of Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, emerging on the north ridge a short distance below the summit.

This feature is known as Collie’s Ledge, after Norman Collie, an English doctor and climber who explored the Cuillins in the late 19th century with his Scottish friend and guide John Mackenzie. In fact, the ledge was discovered in 1887 by Mackenzie and an Irish climber called Henry Hart. Since Sgurr Mhic Choinnich is itself named after the Gaelic form of Mackenzie, some people, including the official Scottish Mountaineering Club’s guidebook, Skye Scrambles, call it Hart’s Ledge.

Collie’s Ledge or Henry’s Ledge? It would perhaps be better known as Willie’s Ledge, since it’s put the willies up many a hillwalker.

I enjoyed it very much. Once onto it, there were no high steps that bothered my knee. In places it was even a path, though it was a path that only the cycling lunatic Danny MacAskill has ever thought of taking a pushbike along (during the filming of his horror flick The Ridge which also featured him carrying his bike unroped up the Inaccessible Pinnacle).

We reached the north ridge and turned up a narrow chimney. From there it was only ten minutes of scrambling to the summit of Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, which we reached in cloud at 1.15.

We were now alone in the mist. All the other climbers had raced ahead of us as I hobbled along behind them. I had no regrets about abandoning the traverse. There was still an enormous amount of scrambling over three Munros and several tops to reach An Dorus, and my knee was enduring a lot of pain. I was satisfied with our two Munros. Even though we had climbed them both before, this had been a different route. There had been interesting scrambling as we filled in the gap between the two peaks.

We still had some tricky scrambling down Sgurr Mhic Choinnich’s north ridge, then a big scree slope down into Coire Lagan. Dave ran down this, and we pretended not to see when he fell over. I took it more carefully, but by allowing the stones to slide beneath me, it was easier on my knees.

But there was still one twist. On the easy trail back to Glen Brittle, with the dark peaks of the Isle of Rum rising across the water, I got carried away with the day’s eventual success. While racing to keep up with the others, I felt my knee lock again as it had above Kinlochleven (see my previous post).

Whatever injury I had done then, I had now done for a second time. On that occasion I had needed three days to recover, and the following day I had barely been able to walk. Once again, my pace slowed to a crawl.

Edita waited for me, but I arrived back at the car in a bleak mood. Dave’s choice of route had enabled us to salvage an enjoyable day out of initial failure, but was this now going to be my only climb?

We still had two more days of good weather, but would I be able to continue?

To be continued… and you can see all my photos from the trip here.

Norman Collie did a lot of exploration in my neck of the woods (Canadian Rockies) in the late 1890-early 1900s.

Ascended many peaks and named one after Alfred Mummery and an adjacent peak he named Nanga Parbat after the Pakistani mountain on which Mummery died.

I recommend reading Collie’s book, Climbs and Explorations in the Canadian Rockies which can be found in an electronic version on Kobo books in Canada.

Yes, indeed. I have a friend who is mad for the Canadian Rockies, who has also recommended this book.

Your article brings back 50 year old memories, many thanks.