As coronavirus lockdown takes hold, the nature writer and reader in English literature at Cambridge University, Robert Macfarlane, has started running a reading group on Twitter about Nan Shepherd’s classic nature book The Living Mountain.

The Living Mountain appeared in a previous blog post of mine, of recommended mountain writing that isn’t about climbing. Ever since I first read it I have known that it’s a book I want to read again and learn about more deeply. As soon as I spotted Robert’s tweet announcing the reading group, it was a no-brainer to join.

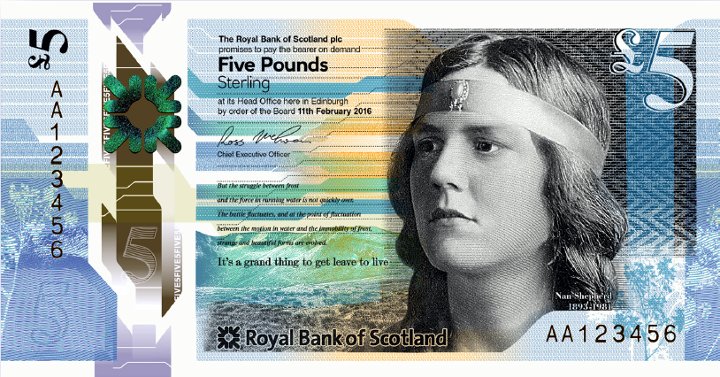

Nan Shepherd was an English teacher and keen hill walker who spent a lifetime exploring the Cairngorm Mountains around her home. She wrote The Living Mountain in the 1940s, but it wasn’t published until 1977, four years before her death. It has since come to be regarded as a classic of nature writing, and by 2016 she had become so acclaimed in Scotland that she even appeared on a Scottish £5 note.

The Cairngorms in north-east Scotland, is Britain’s largest concentrated mass of high mountains. Essentially a single giant plateau with many peaks and valleys, they are the only place in the UK where you can walk for many miles without dropping below 1,000m. They contain 5 of our 6 highest mountains (though not the highest, Ben Nevis). For the most part they are gently rolling with heather-clad moor and peat bog on their flanks, though there are many ridges and crags. The highest parts of the plateau are a mass of broken granite. If you want to know more, then this thread is a great introduction.

My own acquaintance with the Cairngorms has been fleeting, but enough of an introduction to feel that I know them. I spent a week exploring the wild northern peaks in 2006, and have returned to the more cosy southern side around Braemar a few times when visiting my brother, who lives near Aberdeen.

But the sum of my knowledge is barely a fraction of what can be found in any single chapter of The Living Mountain. The book is short — only 30,000 words or 80 pages — but not one word is wasted. Each chapter explores an aspect of the natural world, from the plants, animals, landscape and geology, to more esoteric topics such as water, frost and light.

The reading group meets every two days to explore a chapter of the book. The chapters are short, only 5 or 6 pages, so it’s easy to keep up, even if you are a slow reader like me and have to concentrate hard in order to absorb it all.

For the next hour, Robert poses a series of questions about the particular chapter we are discussing. He doesn’t drive the conversation, but steps back and watches it grow, interjecting only occasionally when someone makes a point that he wishes to build on. Contributors are encouraged to post photos, not necessarily to illustrate their point but more to inspire.

There are hundreds of responses to each question, so it’s not possible to follow everything that’s being discussed. I have followed it by scanning down the thread beneath Robert’s question, then opening out the sub-threads if someone’s comment has caught my eye.

But before I give some examples, I have a confession to make. I’m very much a proponent of the plain-language school of writing. Although I have a decent standard of written and spoken English, I’m a science graduate and information management post-grad.

I was never much of a scholar of the arts, and have a mischievous streak. I tended to annoy school English and English literature teachers by doing what these days would be described as ‘trolling’. I’m rubbish at any form of literary criticism, and my essay-writing skills would shame any student of literature.

Despite this, I have somehow become a professional writer, both as an author of lighted-hearted, humorous travel books, and in my day job as a digital communications consultant who trains employees of big organisations in content marketing and communicating in plain language.

I’m not a big fan of poetry, and I don’t have much patience for any form of writing that you have to read several times to understand. That being said, I believe that lyrical writing, profound meaning and clear language can happily coincide. Not many people can do this — I certainly don’t claim to — but those who can are the great writers whose writing speaks to people across all classes and cultures.

Anyway, sorry for the long preamble. I guess it’s a long-winded way of saying that if I end up making a fool of myself, then this is why. I certainly feel a little out of my depth mingling with the many far more erudite people contributing to Robert’s reading group. I haven’t felt confident enough to contribute myself, and have been content to follow the comments and ‘like’ the ones that resonate.

The Living Mountain is not an easy read. While some words flit off the page and are easily absorbed, there are many paragraphs that I have to read several times in order to fully understand them. There are even some that I can’t relate to at all, but you don’t have to understand every word to get something out of it.

Before joining the discussion, I started by re-reading the first chapter, ‘The Plateau’. I have the book in old-fashioned paperback form, so I took photographs of passages that struck me. Without any guidance, I was probably concentrating too much on the surface words instead of looking underneath.

For instance, I bristled at the following line:

Circus walkers will plant flags on all six summits in a matter of fourteen hours. This may be fun, but is sterile.

I took this as a snooty dig at the sport of Munro bagging (I don’t know how prevalent Munro bagging was in the 1940s). But on the next page came this:

It is, of course, merely stupid to suppose that the record-breakers do not love the hills. Those who do not love them don’t go up, and those who do can never have enough of it.

Nan was herself a climber who often visited summits when she was younger. But later in life, she preferred to explore the places underneath at a slower pace. Many of the people in the reading group were looking for deeper meanings in other places, and understood what I had not. They were even able to relate her writing to the present age:

The Living Mountain is a book full of deeper meanings. Looking for hidden meanings is not something that comes naturally to me. I was born and brought up in Yorkshire, where culturally we are raised to think and talk quite directly. In my day job as a communications consultant, hidden meanings are a no-no. You want your audiences to understand you, and don’t want to risk any of them giving your message a different interpretation.

Other readers taught me that I need to let go of this mindset to understand Nan’s words. Towards the end of the chapter, she talks of how ‘the short-sighted cannot love mountains as the long-sighted do’. Again, I took this literally. Of course those with good long-distance vision can see more of the landscape when standing on a mountaintop, but isn’t this a little discriminatory? In any case, you can fix it with a good pair of glasses.

But other readers looked beneath the surface and took this to mean, not short-sighted of vision, but short-sighted of mind:

In the second chapter, ‘The Recesses’, about the hidden corries and valleys, there is a moment when Nan walks out into the waters of Loch Avon and finds them crystal clear. Suddenly she realises she is standing on the edge of a shelf, and the waters give way to deeper blackness beyond. She steps back and talks about having escaped from a deadly peril:

I could, of course, have overbalanced and been drowned.

To which my immediate thought was: you mean she can’t swim?

Other readers ignored the literal meaning and instead explored the sense of fear she felt, one I might easily have felt when standing on the brink of a tall cliff:

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Going back to the first chapter, Robert kicked off the reading group with a very general question. It produced some interesting replies that caused me to wonder at the writing a little more.

Many people remarked on the language, and her use of particular words. She talks about a particular quality of light in the Cairngorms, which she describes as ‘luminous’. Some quoted other poets in their replies:

There is a discussion of ‘feyness’, a lovely old-fashioned word that I cannot recall ever having seen anywhere else:

Onto Chapter 2, ‘The Recesses’, which we discussed on Monday. Here Robert’s questions became more specific, which seemed to provide less scope for exploration. Even so, the discussion led me to think differently right from the start (for example, with his own reference to a raven’s bill).

![Robert Macfarlane

@RobGMacfarlane

...This is Loch Coire an Lochan, the "secret" loch of which Nan writes. I've swum here one golden September, skied across its frozen surface one March. A shadow the form of a raven's bill falls across it at a certain time of day... [2/3]

Robert Macfarlane

@RobGMacfarlane

...and my first thought/question concerns the contrast Nan draws between 'summit' and 'recess'. Was this striking or counter-intuitive to you? And what's the role of gender here; is Nan writing openly against a 'male' tradition of mountain-conquest, or just...making her own way?

8:21 PM · Mar 30, 2020](https://i0.wp.com/www.markhorrell.com/wp-content/uploads/1244706383481708546.jpg?resize=675%2C1024&ssl=1)

When I first read this, my smutty, literal mind wondered if by summit and recess he was referring to our sex organs. Just as well that I didn’t contribute to the discussion.

But of course, there was a deeper meaning here too. While few readers seemed to agree that Nan was writing about gender (in the sense that mountain conquest is seen as a masculine thing, while pottering and exploring the lowlands can be seen as more feminine), the question led to another interesting discussion about language:

I could go on; I have only tickled the surface here, but I don’t want to bore you. If you want to know more, then the best thing is to explore the conversations yourself. There is a gold mine to be discovered.

There may also be something in this reading group that I can take away as a writer, but so far it’s not been about that. I will never be half as good a writer as Nan Shepherd, and my writing style will always be more direct. At the moment I don’t feel at all inclined to change that, and I may alienate some of my readers if I try.

Nor do I see the group as improving me as a literary critic. Although I’m getting a lot of satisfaction out of reading other people’s thoughts, my own brain doesn’t work this way, and I’m OK with that.

But the reading group is definitely helping me to understand this particular book, and I guess that’s the main purpose of any reading group. And in the case of The Living Mountain, this has one huge benefit. Nan Shepherd had great talent as a writer, but she had an even greater talent as an observer of nature. By understanding this book more deeply, it will change the way I look at the land and its inhabitants.

I had already noted this description of a hidden lake beneath the summit of Braeriach, where Nan uses three of her senses — touch, sound and sight — to experience it.

In the second chapter, there is a passage where she bends over and looks between her legs to observe the world from upside down (if you can hold that image without sniggering). She noted that:

In no other way have I seen with my own unaided sight that the earth is round.

I went out and tried that in my garden. I felt a bit of a fool and I certainly couldn’t see the curve of the earth, but the world looks different from high on a mountain. In any case, Nan probably didn’t intend this passage to be taken literally either. It was another prompt for the reader to see the world differently. That’s one of the key points to take away from this book.

Robert Macfarlane’s reading group convenes every two days at 8pm UK time, and you can follow it via Robert’s Twitter profile @RobGMacfarlane, or via the hashtags #TheLivingMountain and the slightly less pleasant sounding #CoReadingVirus. We are only up to Chapter 3 (which takes place tonight), so there’s still plenty of time for you to get involved.